THE CASANOVA TOUR

by Pablo Günther

POSTING, ALPINE PASSES, SHIPS: Casanova and Travelling in the Century of the Grand Tour.

(continuation of part I :) The Post: National Peculiarities - French Regulations for Travelling Post - Costs : Six thousand Posthorses / 1 Posthorse / Stage-Coaches / Carriers / Hired Carriages / Cambiatura / Taxis / Purchase of Carriages- Rich and Poor Private Carriage Travellers - Speeds - Roads - Alpine Passes - The Mont Cenis - Ships . (Part III : Travelling Carriages)

Around 1725 most of the European states had their own national posts but there were a few exceptions and peculiarities:

In Switzerland, there were different private post companies which did not rent horses to travellers. Casanova states briefly (GmL,vol.VI,p.98) : "in Switzerland, there were no posts". Nevertheless, he could drive in his own carriage through the country, evidently providing himself with horses from carriers.

The official post of the Holy Roman Empire was the Thurn und Taxis Reichspost, founded in 1490. This company provided the South, the West, some middle states and the Austrian Netherlands. Austria, Prussia, Saxony, Hessen - Kassel, Hannover, Brunswick, Mecklenburg and larger Empire- or Hansa-cities had their own state posts.

In Italy, there were six large state posts:

1. The Austrian Post, which provided the Duchies of Milan, Mantua and Tuscany;

2. The Roman Post of the Ecclesiastical State;

3. The Post of the Kingdom of Sardinia (Savoy, Piedmont);

4. The Post of the Kingdom of Naples;

5. The Post of the Republic of Genoa;

6. The Post of the Republic of Venice.

In addition, there were the smaller posts of Modena and Parma, as well as the Thurn und Taxis Reichspost (also called "Flandrian Post") in some other cities.

.

I give here an excerpt from the "Extraits des Règlements sur le Fait des Postes" of the 1781 guide of post stations "Liste Générale des Postes de France" (italics, "postillon" and the &: original writing). The regulations of most countries' post companies were similar to the French.Weights & loading with trunks, suitcases, boxes & porte-manteaux.

Table of prices for post horses. "Liste Générale des Postes de France", Paris 1781. - Photo: Museum Achse, Rad und Wagen, Wiehl.

The payment for travelling post was calculated by "posts" or "stages", the distances between two stations or relays. They differed in each country:Costs.

England: ................ 8.0 km, 5 English miles, or 1 "(post-)stage".Example: when the real distance between two post stations (the post-stage) in France was 3 miles, instead of the usual 2, one had to pay for "one and a half posts". Nugent states (vol.IV,p.17) : "The post-stages are seldom above one post and a half, or two posts long."

France and Holland: 9.0 km, 2 lieues / French miles, or 1 "poste".

Russia: ................ 10.7 km, 10 versts, or 1 post.

Italy: ................... 12.0 km, 8 Italian miles, or 1 "posta".

Germany: ............ 15.0 km, 2 German miles, or 1 "Post".

To give an idea of the costs involved, these distances have been converted into kilometres and the prices into a single currency (here the English Penny (d.) of the eighteenth century which had about the same purchasing power like the Euro in 2002 (cf "Currencies").Costs for 1 Posthorse.

Thus, a seat in a stage coach cost between 1 and 2 Pence per kilometre, and the hire of one post horse from 1.38 to 3.33 d., according to the country.

This was very expensive: for only 2 kilometres in a German stage coach, one had in 1766 to pay about as much as for a kind of "Big Mac" in Hase's cook-shop in Berlin, namely 2.70 d. (cf again "Currencies", costs in Berlin).

Today (April 2002), for the same price as for a real Big Mac (2.70 Euro), one can use the German railway over 19 kilometres; or one can buy in Germany enough petrol for a small car to travel about 40 kilometres.

Casanova, who most of the time had to hire 4 post horses with his travelling carriages, would on the average have only been able to travel 350 metres for that account of money (2.7 d.)...Six thousand Posthorses.

Until 1774 (period of the memoirs), when using the services of the travelling or "driving post" (in German: Fahrpost), Casanova took stage coaches only 22.3 per cent of the total distance, while for 77.7 per cent he travelled posting (German term: Extra-Post), that means with his own (C 1-14), hired (L), or his friends' (K) carriages, hiring post horses.

Extra-post travellers could additionally use post roads where stage coach lines did not operate, but which had a mail service.

In those times posting was the most comfortable, but also the most expensive, method of travelling, equivalent today to flying in a private aeroplane.

Altogether (that means until 1798), in his own or hired travelling carriages, Casanova covered 30,665 kilometres.

On average, he had to take 3.6 posthorses which were exchanged after - again on average - 18 kilometres. Thus, he paid about 250,000 Pence (converted) when changing horses 1,704 times for 6,134 of those post horses...

To distinguish between simple open carriages ("wagons") and more comfortable closed carriages ("coaches").1 seat in the "Newberry flying stage coach" (The Daily Post, 27-4-1727)

A carrier was called in France "voiturin", in Italy "vetturino" (or Procaccio in Venice) and in Germany "Landkutscher". Everywhere in Europe carriers complemented the services of the post stations. They were not allowed to hire post horses but had always to use the same mules or horses; in consequence their speed was very slow.Venice (J C Goethe, 1740): 2 persons including food, per day

Travelling carriages and horses were usually hired from post-stations, and town carriages from private entrepreneurs.France (Casanova, 1763): basic price (without horses) Paris - Lyons 144 Francs; per km: ........ 3.13

The Cambiatura was a system in use in north and middle Italy whereby Ministers of the Post, accorded travellers who requested it, the privilege to save on costs by hiring post carriages which, to the discomfort of the traveller, had to be exchanged at every stage. In Venice this system was known as the "Bollettino". Casanova's friend Simone Stratico stated (p.66) that he saved one third of the usual fees in Milan in 1770. If postillons were required, they had to be paid for out of a traveller's own purse.Tuscany (Smollett, 1764): per post and 2 horses 10 Paoli; per km: .................................... 5.0

This privilege began a long tradition; up until 1991 tourists travelling by motorcar in Italy could buy in their own country credit notes for petrol subsidized by the Italian Government.

Carriages and their coachmen for hire, licensed by the city governments. They were called e.g. hackneys, fiacres or Droschkes. First established in Rome at the end of the 16th century (Wackernagel, in: Treue, p. 213), after a few decades they also appeared in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and many other cities.Paris (Casanova, 1759): fiacre (no specification) 24 sols = ................................. 12.0

Purchase of Carriages.

Paris & Calais (Smollett, 1763): a second-hand

travelling

coach: 35 Guineas ......................... 8,400

Lyons (Casanova,

1763): a second-hand two-wheeled French

Chaise de Poste: 40 Louis

d'or .. 9,600

Rome (Nemeitz, 1725): a new, simple sedia

(two-wheeled "Italian chaise"): 30 Scudi ............... 1,800

Cesena / Bologna (Casanova,

1749): a second-hand

English Post-Chariot:

200 Roman Sequins =

....................................................................................................

21,600

Bologna (Casanova,

1772): a second-hand (English?)

coupé: 300 Roman Scudi ....................

18,000

Geneva (Casanova,

1762): a second-hand English Post-Chariot: 100 Louis d'or,

plus a coach worth about 6,000 d.

..................................................................................

30,000

Berlin (Nicolai, 1781): a new travelling "Vienna

Carriage", a four-wheeled

four-seater, open: 70 Ducats

............................................................................................

8,400

Mainz (Casanova,

1783): a second-hand four-wheeled and two-seater chaise: 5 Louis

d'or ...... 1,200

London (Goodwin, 1756 - 1799): new Post-Chaises

and Post-Chariots,

with basic equipment: prices around

100 Guineas .............................................................

24,000

luxury model: at most 200 Guineas

.................................................................................

48,000

London (Lamberg [Marr 2-71], 1790): State-coach

for the Empress

Katharina II, made by John Hatchett: 6.000 Rubel

............................................................ 324.000

London (La Roche, 1785): State-Coach for

the Nabob of Arcot,

made by Hatchett: 5,000 Guineas ...................................................................................

1,200,000

A rather rare method of travelling was always using the same carriage-horse(s). In this way, travelling very slowly, Mozart's most famous librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, and his wife Nancy arrived at Dux in 1792, to see their old friend Casanova. Together they drove to near Teplice where the carriage broke down and had to be sold. Casanova acted as agent achieving a price of 60 piastres (3,600 d.), keeping back for himself a commission of 2 Sequins or 6% (220 d.) to pay for his return journey.Rich and Poor Private Carriage Travellers.

However, even that did not reach the height of luxury travel. Three days

later (26th June) Clary noted in his diary:

However, even that did not reach the height of luxury travel. Three days

later (26th June) Clary noted in his diary:

Only on one occasion did Casanova complain about a bad road; that was between Magdeburg and Berlin when he was angry about the loss of time. In contrast, he praised the "excellent" roads in France and Italy, which enabled him to travel fast. Driving day and night in his own carriage, he covered up to 240 kilometres in 24 hours.Speeds.

Four countries had some highways (causeways, chaussées; fastened artificial roads): France, England, Italy, and all the United Netherlands (Holland) which had many highways, together with a great network of waterways. Other countries began chaussée building only at the end of the century, or later.Roads.

In the Alps, the first road over a pass, which was broad enough and not too steep for carriages, was built in 1387. This was the Roman Septimer Pass near St. Moritz which connected Chiavenna (or Milan) with Chur (the Romans had excellent carriage roads but only mule tracks over the high passes).Alpine Passes.

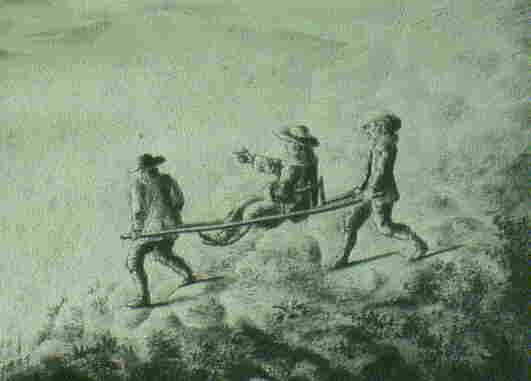

Apart from the Semmering (and the Brenner in 1783), Casanova found only mule-tracks on the passes. Travellers usually let themselves be carried by "mountaineers", horses or mules. Stage coaches or other commercial wagons, were left back at the foot of the mountain. Private carriages were taken to pieces and transported over the pass; Casanova went through this routine on six different occasions.year* name height (meters) connections (Casanova's crossings)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1728 .. Semmering ...................... 900 .... Vienna - Graz (3)

1772 .. Brenner ........................ 1,374 .... Innsbruck - Bolzano (2)

1782 .. Tenda ........................... 1,871 .... Nice - Turin (1)

1803 .. Mont Cenis .................. 2,083 .... Lyons - Turin (6)

1905 .. Grand Saint Bernard .... 2,473 .... Lausanne - Turin (1)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[* year of road-building]

* * * The Mont Cenis.

For thousands of years Mont Cenis was the most important pass of the Western

Alps. It was considered the easiest to cross (cf Michel de

Montaigne, in the year 1581) and for this reason Grand Tourists

almost always chose this pass on their journey from France (Lyons) to Italy

(Turin).

For thousands of years Mont Cenis was the most important pass of the Western

Alps. It was considered the easiest to cross (cf Michel de

Montaigne, in the year 1581) and for this reason Grand Tourists

almost always chose this pass on their journey from France (Lyons) to Italy

(Turin).

The village of Grand Croix, the only surviving settlement on the Mont Cenis. In the background is the wall of the reservoir. - Photo: PG.

Ships.

Antonio Canal was working on his painting "Il Bacino di San Marco" (here a cutting) just at the time when nine year-old Casanova set off for his first journey. This happened on a postboat called Il Burchiello, going on board at the Piazzetta, crossing the lagoon to Fusina and from there being towed (drawn by horses) on the river Brenta to Padua. There was no Grand-Tourist who did not praise this comfortable conveyance in his letters. - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. From: Briganti, Glanzvolles Europa. Photo: PG.

.

.

Il Burchiello today. As in Casanova's time, passengers can enjoy the view of the magnificent villas on the riverbanks of the Brenta. Here the boat is passing Mira on its way to Padua (Photo left: PG). - The lock of Dolo, painting by Antonio Canal. Today the house in the lock contains a restaurant.

A model of a felucca, in the Museu Maritim at Barcelona. This was a coastal ship used everywhere on the Mediterranean Sea. Casanova took some between Antibes, Genoa and Lerici. - Photo: PG.

As a cadet in the Venetian Army, the sixteen year-old Casanova voyaged as far as Constantinople on board a galley. - An exact copy of the galley used by Don Juan d'Austria at the sea-battle of Lepanto (1571). Museu Maritim, Barcelona. Photo: Pere Vivas.

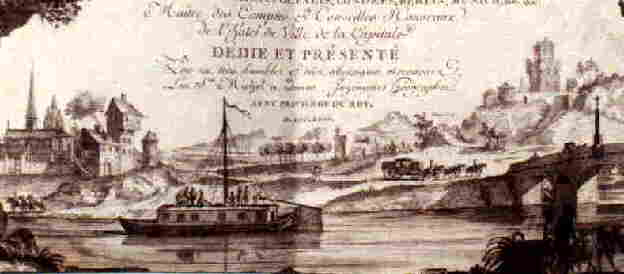

German Ferry. Cutting of a view of Speyer on Rhine by Matthaeus Merian, about 1640. - Photo: PG.

Draw-boat and stage coach meet on a bridge in France. E. g. in 1760, Casanova took such a boat on the rivers Isère and Rhone from Grenoble to Avignon (his travelling carriage was on board, too). - From: L'Indicateur Fidèle, Paris 1764 (cutting). Deutsches Postmuseum Frankfurt a.M. - Photo: PG.

...

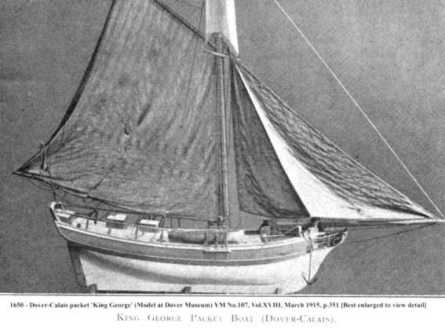

... Between Calais and Dover, Casanova used or chartered postboats, also called packetboats. - Picture in black and white: "King George Packet Boat (Dover - Calais)", about 1650, model at Dover Museum. / In Colour (full size and detail): "Dover-Calais Packetboat about 1815", recent painting and copyright by the English artist John Michael Groves RSMA (Royal Society of Marine Artists) . Thanks to Hector Zerbino and Derek Oakes for sending these excellent pictures.