A HANDBOOK FOR

THE USE OF THE PRIVATE TRAVELLING CARRIAGE

IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY EUROPE AND AMERICA.

BY P A B L O G Ü N T H E R .

* * * * * * * *

Lister Chaise

1755 until todayGiacomo Casanova

born 2nd April 1725 in Venice

died 4th June 1798 in Dux / Bohemia

* * *

* * *

Robert Goodwin, Taynton casanovist

Gillian Rees, Eastbourne casanovist -

with many thanks for correcting the text of the first editions (1995 / 96)

(now existing mistakes are my own).

Rosalind Westwood, Halifax carriage museum director

Gérard Cazobon, Compiègne carriage museum director

Marie-Francoise Luna, La Tronche casanovist

Dr. Georg J Kugler, KHM, Vienna carriage museum director

Annunziata von Lutterotti-Diebler & Wolfgang Diebler, Vienna

Richard C V Nicoll, Williamsburg carriage museum director

......

......  ......

......

(Part I )

Forewords.

A Favourable Thunderstorm.

POSTING, ALPINE PASSES, SHIPS:

Casanova and Travelling in the Century of the Grand Tour.

Introduction.

Casanova's methods of travelling.

Table of Casanova's Journeys I. 1725-1774.

Table of Casanova's Journeys II. 1774-1798.

Manners of Travelling, by Thomas Nugent.

(Part II )

The Post: National Peculiarities: Switzerland, Germany, Italy.

French Regulations for Travelling Post.

Costs: 6000 Posthorses. Posthorses. Stage-Wagons and Stage-Coaches. Carriers.

Hired Carriages. Cambiatura. Taxis. Purchase of Carriages.

Rich and Poor Private Carriage Travellers.

Speeds. Roads. Alpine Passes. The Mont Cenis.

Ships.

(Part III )

TRAVELLING CARRIAGES.

Carriages Mentioned by Casanova.

Carriages in Virginia and England.

Notes on the Goodwin-Report.

Two-Wheeled Carriages.

Chair, Chaise, Calash.

(Part IV)

Four-Wheeled Carriages.

Chaise, Calash, Phaeton.

Carosse, Carosse-Coupé.

Landau.

Berlin, Berlin-Coupé, Berlin-Calash, Berlin-Phaeton, Berlin-Chaise.

English Coach, English Coupé.

German Travelling Carriage.

Stage-Wagons and Stage-Coaches.

Steel Springs.

(Part V)

The English Coupé or Post Chariot.

From Casanova to Napoléon I.

Transportation of Dismantled Travelling Carriages.

Napoleon's Waterloo - Post Chaise.

A History of the English Coupé in the 18th Century.

(Part VI )

Casanova's Carriages.

I. His Travelling Carriages between 1749 and 1772:

Carriages 1. - 7.

(Part VII)

Carriages 8. - 14.

II. His Carriages in Paris.

(Part VIII )

III. His Travelling Carriages 15. - 17. from 1773 onwards.

Correspondence when Selling a Used Carriage.

(Part IX )

POST ROADS.

Statistics. Legend.

Casanova's Travel Routes.

1. The Sea Routes.

(Part X)

2. London - Naples .

(Part XI)

3. Vienna - Venice. Casanova's Postal Memorandum. 4. Venice - Geneva .

5. Frankfurt - Dresden 6. Bologna - Augsburg.

(Part XII)

7. Augsburg - Paris 8. Vienna - Paris .

(Part XIII)

9. Paris - Amsterdam 10. Amsterdam - Geneva 11. Brussels - Geneva .

(Part XIV)

12. Geneva - Florence 13. London - Moscow .

(Part XV)

14. Königsberg - Dresden 15. Paris - Madrid 16. Madrid - Aix-en-Provence .

17. Vienna - Berlin .

(Part XVI )

CURRENCIES.

Mr. Nugent's Rates of Exchange.

England. Netherlands. Germany. Italy. France. Summary. Literature.

Casanova's Monetary Conditions.

(Part XVII )

APPENDIX.

Bibliography.

Index of Persons.

(Part XVIII)

Index of Post Stations.

I. by Gillian Rees

The fascination and interest created by Casanova's Story of My Life seems to be never - ending. Not many years after its initial publication in German in 1822, the first fundamental examination of his memoirs appeared in 1846, and from that time onwards the volume of works concerning Casanova has steadily grown. Despite more than 400 editions of his memoirs which have now been produced in over 20 languages, volumes of his letters, reprints of his other works, and the recent publication of many inédits from the archive material left at his death, Casanovists are still busy researching various aspects of his life.

Over 3,650 books and articles have now been written about this extraordinary man covering his sojourn in different parts of Europe and particular periods in his life; his interest in women, food, the theatre, medicine, chemistry and the cabala, to name but a few; and the varied men and women that became associated with him. Many books have dealt with critiques of his work, others have attempted a psychological analysis of his character. A mammoth undertaking is now under way to make available for the future computer copies of the papers left at his death.

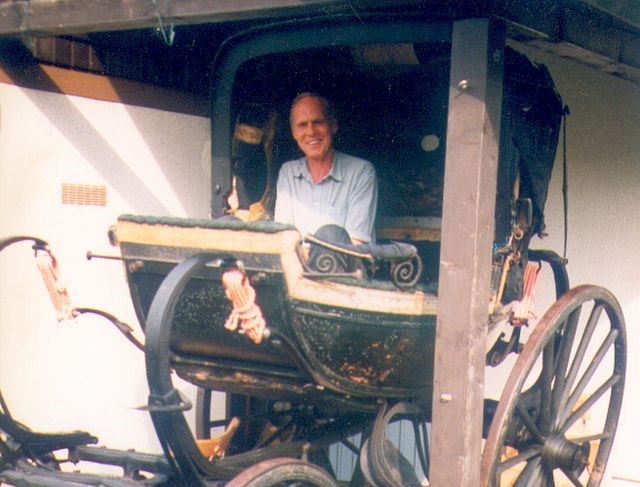

The author of this present volume has combined his considerable knowledge of historic carriages and his interest in the memoirs to add yet more to the rich tapestry of our knowledge about Casanova. A unique book describing the private carriages that Casanova owned, the roads he travelled on throughout Europe, with all the customs and costs that such travel imposed in the days of the Grand Tour. Casanova was one of the very first people to leave us a description of such extensive travelling in his own carriage, and the author has himself travelled over 10,000 kilometres in his research of the post roads and posting inns that Casanova used. This book brings together for the first time a history of the developing use in the 18th century of the private travelling carriage, in particular of the English Chariot, with an analytical account of Casanova's great journeys.Gillian Rees, Eastbourne, December 1995The age of the motorcar is separated from that of the horse-drawn carriage by the grand time of the railway. Between 1860 and 1910 this ingenious, but public transport, was completely unrivalled for long distance travelling; only a few of the super-rich preferred to continue travelling in their own posting chariots.II. by Pablo Günther

In Germany, the common use of the automobile did not start until the 1950s. That is why, after a hundred years of travelling on the railways, we have forgotten the former use of the private travelling carriage. At most we remember the "romantic" stage coach of the 19th century, with the postilion merryly blowing his horn. But the century before that now seems very remote; and furthermore, travelling by private carriage in that time has remained largely unresearched - a notable gap in travel and carriage literature.

Indeed, the pleasure of riding in one's own carriage, and of the freedom and mobility that it gave, is not a pleasure of life reserved only to today's car drivers. The time when it began can be clearly determined: it happened when the coach - after two hundred years - was technically improved, and in consequence able to leave the cities and travel large distances on the wide network of post roads which by then existed.

The first known devotee of this modern way of travelling is Giacomo Casanova. This quite clearly means that the adventurer from Venice and world famous lover was also the first great user of the modern private carriage of whom we have complete knowledge, thus being the forerunner of all of us motorists.

Like millions of people, I love driving my car. My present one is my seventeenth - Casanova had nineteen. Having my "carriage" ready to roll in front of the house, I share with Casanova a good feeling in this regard, too.Pablo Günther, Hergensweiler, May 1996

[From: Giacomo Casanova, "A History of My Life", translated by Willard R Trask, published by Longmans, 1967 - 1970, vol. I, chapter 5, pages 152 - 155.A Favourable Thunderstorm;

Or, The Story when Casanova Became Casanova.

Pasiano di Pordenone, May 1742.... through the forest of Cecchini ...From the Villa Gozzi in Visinale (photo: PG) ... On Ascension Day we all went to call on Signora Bergalli [Gasparo Gozzi's wife, at their villa in Visinale], a famous ornament of the Italian Parnassus. When it was time to return to Pasiano the tenant-farmer's pretty bride started to get into the four-seated carriage in which her husband and her sister had already taken places, thus leaving me all by myself in a two-wheeled calash. I protested, loudly complaining of her unjust suspicions; and the company all insisted that she must not insult me in this fashion. At that, she came in with me, and upon my telling the postilion that I wanted to go by the shortest route, he left all the other carriages and took the road through the forest of Cecchini.

........................................................................................................................................... . .

... in a two-wheeled calash ... [Picture left: engraving by Jules Adolphe Chauvet, 1876. From: Casanova in Bildern, Munich 1973. - Photo right: PG.]............................................................................................................................................

The sky was clear, but in less than half an hour a storm came up, one of those storms which come up in Italy, last half an hour, seem to be trying to turn the earth and the elements upside down, and subside into nothing, with the sky cleared and the air cooler; so that usually they do more good than harm.

"Oh my God!" said the bride. "We are in for a storm."

"Yes, and though the calash is covered, the rain will ruin your dress, I'm sorry to say."

"What do I care about my dress? It's the thunder I'm afraid of."

"Stop up your ears."

"And the lightning?"

"Postilion, take us somewhere where we can find shelter."

"The nearest houses," he answered, "are half an hour from here, and in half an hour the storm will be over."

So saying, he drives calmly on. There is a flash of lightning, then another, thunder rumbles, and the poor woman is shaking all over. The rain comes down. I take off my cloak to use it to cover us both in front; and, heralded by an enormous flash, the lightning strikes a hundred paces ahead. The horses rear, and the poor lady is seized by spasmodic convulsions. She throws herself on me and clasps me in her arms. I bend forward to pick up the cloak, which had fallen to our feet, and, as I pick it up, I raise her skirts with it. Just as she is trying to pull them down again, there is another flash of lightning, and her terror deprives her of the power to move. Wanting to put the cloak over her again, I draw her toward me; she literally falls on me, and I quickly put her astride me. Since her position could not be more propitious, I lose no time, I adjust myself to it in an instant by pretending to settle my watch in the belt of my breeches.

POSTING, ALPINE PASSES, SHIPS:

Casanova and Travelling in the Century of the Grand Tour.

Two young ladies relax while passing along the Cote d'Azur on their Grand Tour to Rome in 1860. They are travelling in an English coach similar to the one shown in the picture below. A hundred years earlier, Casanova used to travel in the same way, relaxed and sitting in an English carriage.

.

Introduction

The term "Grand Tour" originated in Great Britain in the 17th century. It designated the "round trip" over Continental Europe - especially in Italy - which was considered an essential final polish for the cultural education of a British gentleman. Great Britain thus became - and remained so until the upheaval of the 2nd World War - the world's most prominent "tourist" nation.(Translation by Hector Zerbino.)

The goal of most Grand Tour travellers was to reach Italy as directly as possible, so that a fairly "standard" itinerary was developed very soon. The British "tourists" usually crossed the English Channel by the Dover-Calais packet-boat, then travelled through France via Paris and Lyons. The Alps were crossed by the Mount Cenis pass in order to reach Turin, the first main Italian goal of the Tour. Thereafter the trip continued via Piacenza, Parma, and Bologna, then over the Apennines to Florence, and finally via Tuscany to Rome.

After Rome, a further trip to Naples was also considered "mandatory". On the return from Naples the travellers usually proceeded to Venice, visiting on the way the basilica of Loreto, a famous pilgrimage site near Ancona. From Venice they would continue either to Switzerland or to Bavaria via the Tyrol. The closing journeys of the Grand Tour were the Rhinelands and the Low Countries. More daring travellers would of course venture much farther, either east to Austria, Saxony, Brandenburg, and so on, or west to Spain and Portugal.

.

These "pleasure" travels (i.e., carried out for neither commercial nor official reasons) required two things in order to be carried out in acceptable conditions: the existence of adequate roads, and the possibility to change horses at regular and frequent intervals.

Regular, public transport services, called "cursus publicus" or "cursus vehicularis", had already been created during the Roman Empire, but they did not survive its fall. Neither good roads nor horse-changing stations had been available in a general way in Europe during the Middle Ages, but they began to reappear in Italy in the early Renaissance.

The first really long distance Post - course (from the Latin "Posta", derived probably from "equites depositi", i.e., posted riders) in modern Europe was inaugurated in 1492 from Innsbruck to Mechelen (near Brussels). Thereafter road building and post services were continuously developed, and the second half of the sixteenth century saw a significant increase. The travel journal of the French thinker Michel de Montaigne (refer to /montaign.htm) in 1580 contains the first references to post stations for coach horses in Italy and for riding horses in Italy and France, and also to numerous carriage types ("cocchi" and "carrozze") used in Italy for city and inter-city transport. Montaigne found good roads not only in Italy, but also in Southern Germany and in Tyrol (Brenner pass).

.

In the Middle Ages, the usual means of transportation for well-to-do travellers was horse riding, either with their own or rented horses. The transition from horse to coach riding was a long drawn-out process that took place very gradually over approximately 200 years, roughly from the mid-16th to the mid-18th century. In the 1750's carriage builders had finally devised faster and more comfortable coaches, and practically all European cities were already linked by roads with adequate post stations. At that time coach riding, using either one's own coach or a rented one, had clearly become the best option for those who could afford it, which was the case of Casanova during his period of prosperity.

.

The most comfortable and fast method of travelling was nonetheless river navigation, which also remained very important. It was quite usual to have one's coach taken on board, as Casanova did repeatedly.

.

At the time it was already true that the Alps were a link rather than a separation. The roads were of course much more dangerous than nowadays, and bad weather conditions were also more critical. These obstacles, however, should not be overestimated. The following text, taken from Montaigne's journal, concerns the trip from Innsbruck to Bolzano. It was written, or rather dictated to his servant, in 1580 at Brixen:"Monsieur de Montaigne said: All his life he has mistrusted other people's opinions concerning the conditions of life in foreign countries, because everybody uses the customs of his own country as a scale of measurement, and people can seldom see beyond the tower of their own village church. He has therefore paid always very little attention to the advice received from other travellers. But especially in this journey he has had cause to wonder much more at their silliness, because he had been told that the crossing of the Alps would be extremely difficult at this point, since the local customs were very particular, the roads inaccessible, the accommodations barbarian, and the climate unendurable. (…) whereas, if he had been told to choose a place in which his eight year old daughter could take a pleasant walk, he would as readily have chosen this road as a path in his own garden. And as for the inns, he has never seen any region where they were so numerous and so well-appointed, and he has always found accommodation in beautiful towns, well supplied with food and wine, and cheaper than elsewhere."This is the opinion of a positively thinking, reasonable man, who obviously enjoyed travelling very much. Montaigne even asserted shortly afterwards, when he was at Rovereto, that "he has so much pleasure in travelling that he hates the idea that the end of the trip may finally be approaching".

Casanova's travel accounts are the most extensive of the eighteenth century. They show that he travelled always as heartily and lustily as Montaigne, and that he accepted the inevitable difficulties quite as good-naturedly. Despite the enormous differences in speed and comfort, long distance travel was probably as commonplace to him as it is to us.

Casanova's methods of travelling.Casanova covered exactly (or better: at least) 65,140 kilometres in the course of his life. He used all manners of travelling (with the exception of the "cambiatura"). Extremely often he travelled by own or hired carriages:

symbol - kilometres until 1774 - km from 1774 onwards - total - methods of travellingA - 25 - - - - - - - 0 - - - - - - 25 - - - DonkeyTotals: 51,540 - - 13,600 - - 65,140km

B - 30 - - - - - - - 0 - - - - - 30 - - - Sledge (Alps)

Z - 60 - - - - - - - 0 - - - - - - 60 - - - Carried chair (Alps)

T - 110 - - - - - - 0 - - - - 110 - - - Hitch-hiking

M - 220 - - - - - - 0 - - - - 220 - - - Mule

H - 250 - - - - - - 0 - - - - 250 - - - Horse

F - 275 - - - - - - 0 - - - - 275 - - - On foot

? - 1,060 - - - - - 0 - - - - 1,060 [two trips (Venice - Rome 1744/45),not mentioned in the memoirs.] R - 1,280 - - - - 180 - - - 1,460 - - - Boat / ship, on river, lake, gulf

V - 2,900 - - - - - 0 - - - 2,900 - - - Carrier / vetturino

L - 3,475 - - - - 245 - - - 3,720 - - - Hired carriage

K - 3,300 - - 3,050 - - - 6,350 - - - Private carriage of others

S - 8,440 - - - - - - 0 - - - 8,440 - - - Ship, at sea

P - 7,850 - -- 5,255 - - - 13,105 - - - Postwaggon, Stage-coach

C - 22,265 -- 4,870 - - - 27,135 - - - Casanova's travelling carriages

No. year vol. catchword (company) routeTable of Casanova's Journeys.

1. The periods as reported in his memoirs (1725 - 1774).

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I. Early Years of Travelling (age 9 - 20):

1.) 1734 I [and many more] Studies (His mother Zanetta, Grimani, Baffo) Venice - Padua - Venice.

[2. - 6. after researches correcting several times dates and courses of Casanova.]

2.) 1741/42 II Constantinople Venice - Kithira - Constantinople - Corfu - Venice.

3.) 1742 & 1743 I Lucia / Thunderstorm Venice - Treviso - Pasiano di Pordenone - Venice.

4.) 1743/44 I Abbate(Bellino-Teresa) Venice - Ancona - Rome - Rimini - Venice.

5.) 1744/45 I Secretary(Lucrezia) Venice - Rome - Martirano - Naples - Rome - Venice.

6.) 1745 II Corfu Venice - Corfu - (Constantinople?) - Otranto - Corfu - Venice.

II. Time of the Bragadin Pension (age 21 - 44):

7.) 1749 II Magic / Henriette (Henriette) Venice - Milan - Mantua - Cesena - Parma - Geneva - Parma - Venice.

8.) 1750 III Paris(Balletti) Venice - Lyons - Paris.

9.) 1752/53 III Theatre(Francesco Casanova) Paris - Dresden - Prague - Vienna - Venice.

10.) 1756 IV Piombi: Escape (Father Balbi; Mme Rivière) Venice - Munich - Strasbourg - Paris.

11.) 1757 V Intelligence agent Paris - Dunkirk - Paris.

12.) 1758 V Financier Paris - Amsterdam - Paris.

13.) 1760 V Esther / pleasure - journey Paris - Amsterdam - Cologne - Stuttgart.

14.) 1760 VI Escape / pleasure - journey (Mme Dubois) Stuttgart - Zürich - Soleure - Roche - Geneva.

15.) 1760 VII Pleasure - journey (Rosalie) Geneva - Marseille - Pisa - Naples - Rome.

16.) 1761 VII Pleasure - journey Rome - Bologna - Turin - Paris.

17.) 1761 VIII Diplomatist Paris - Augsburg - Munich - Basle - Paris.

18.) 1762 VIII Magic(La Corticelli; Mme d'Urfé; Mimi) Paris - Metz - Paris - Aachen - Sulzbach - Geneva - Lyons - Turin.

19.) 1763 VIII Magic(La Crosin; Rosalie; Marcolina) Turin - Geneva - Milan - Genoa - Marseilles - Lyons.

20.) 1763 IX Direction of London (Adèle) Lyons - Paris.

21.) 1763 IX London(Aranda / Giuseppe; Pauline) Paris - Calais - London.

22.) 1764 X Frederic II (Redegonda) London - Wesel - Wolfenbüttel - Berlin.

23.) 1764 X Catharine II (Zaira) Berlin - Mitau - St.Petersburg - Moscow - St.Petersburg.

24.) 1765 X King Stanislaus (La Valville) St.Petersburg - Warsaw - Crystinopol - Warsaw.

25.) 1766 X After the duel (Maton; La Castel-Bajac) Warsaw - Leipzig - Dresden - Prague - Vienna.

26.) 1767 X Vienna: evicted (Charlotte) Vienna - Augsburg - Ludwigsburg - Spa - Paris.

27.) 1767 X Paris: evicted Paris - Pamplona - Madrid.

28.) 1768 XI Nina Madrid - Zaragoza - Valencia - Barcelona.

29.) 1768/69 XI Assassins Barcelona - Aix-en-Provence.

III. Seeking His Return to Venice (age 44 - 49):

30.) 1769 XI Book-printing Aix-en-Provence - Nice - Lugano.

31.) 1769/74 XI Homesickness(Betty) Lugano - Turin - Naples - Rome - Florence - Bologna - Ancona - Trieste - Venice.

No. year month(s) (manner of travelling*, kilometres) route remarks2. The period from September 1774 until his death in 1798.

----------------------

[* C = Casanova's own carriage; K = private carriage; P = stage-coach; R = ship.]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

IV. Again in Venice (age 49 - 57):

1.) 1774 September (P 200)Trieste - Gorizia - Venice. Arrival on the 14th.

2.) 1776 December (P 400) Venice - Trieste - Venice. "Secret mission".

3.) 1779 June/July (K 490)Venice - Bologna - Forli - Cesena. Return journey via Imola and Bologna to Venice. With Consul Del Bene, sent by the Venetian Inquisitors.

4.) 1780 July (P 90) Venice - Abano Terme - Venice.

V. Seeking a New Home (age 57 - 60):

5.) 1782 Sept./Oct. (P 400) Venice - Trieste - Venice. Sudden departure. Sojourn of one month.

6.) 1783 January (P 700) Venice- Trieste - Vienna. Sojourn in Vienna of about five months.

7.) 1783 June (P 700)Vienna - Trieste - Venice. One week in Udine, another week in Mestre. - Journeys 7. - 10.: Casanova's last "Grand Tour".

8.) 1783 June-Sept. (P,C15,R,K 2,070)Venice - Frankfurt - Spa - Amsterdam - Paris. From Innsbruck to Mainz: his travelling carriage C 15. - November: in Fontainebleau.

9.) 1783 Nov.-Dec. (C16 1,360)Paris - Frankfurt - Regensburg - Vienna. The whole journey with his brother Francesco and in their own travelling coach C 16 "Paris 4".

10.) 1783/84 Dec.- February (P 1,435)Vienna - Prague - Dresden - Berlin - Dessau - Leipzig - Dresden - Brünn - Vienna. From Vienna in 1784/85: Excursions to Meidling Marr 16 F 12, Baden and Wiener Neustadt.

VI. In Count Waldstein's Castle of Dux (age 60 - 73):

11.) 1785 July-Sept. (P,L 620) Vienna - Brünn - Czaslau - Prague - Carlsbad - Töplitz - Dux.

September: Casanova found his final home in Dux.

12.) 1786 July (C17 250) Dux - Carlsbad - Dux. At Count Waldstein's desire and with his carriage - horses [Marr 14 M 1] (his own carriage C17 "Dux" from here on until trip no. 20).

13.) 1786 October (C17 220) Dux - Prague - Dux.

14.) 1786 December (C17 150) Dux - Dresden - Dux.

15.) 1787/88 July '87 - Sept. '88 (C17 660) Dux - Prague - Dux. Casanova was mostly in Prague; at least three trips between the cities. - He met again Da Ponte; 29th Oct. '87: first performance of "Don Giovanni". - Print of "Icosameron" and "Histoire de ma fuite".

16.) 1788 Sept.-Oct. (C17 570) Dux - Prag - Leipzig - Dresden - Dux. October, departure from Dresden: examination by the guard searching a stolen "Magdalaine" [cf. L'Ermitage, revue des litt. et d'art, 15th Oct. 1906].

17.) 1789 January (C17 240) Dux - Prague - Laun - Dux. In Laun he had an accident with his carriage [cf. Intermédiaire viii, pp 31-32: Casanova's letter to his nephew Carlo Casanova]. 27th June 1789: he mentions his own carriage in his "Essay d'Égoisme" [Marr 16-36] (referred to here as C17 "Dux"). - Began writing his memoirs.

18.) 1790 May/August (C17 470) Dux - Dresden - Sagan - Dresden - Dux. Sojourn until August in Dresden. Print of "Solution du problème déliaque". - Trip to Sagan: his letter to Antonio Collalto of 2nd July 1790 from Dresden.

19.) 1791 May (C17 150) Dux - Dresden - Dux.

20.) 1791 September (C17 240) Dux - Prague - Dux. On the sixth: coronation of Leopold II. - 31. 12. 1791 - May 1793: Casanova stayed at Oberleutensdorf (Count Waldstein's textile factory, close to Dux). September 1792: Visit by L. Da Ponte.

21.) 1795 Sept.-Dec. (K 805) Töplitz - Leipzig - Weimar - Leipzig - Berlin - Dresden - Dux. With his beloved whippet "Mélampige II". In December, when he was in Dresden, his brother Giovanni died. [Cf. Marr 16 K 2, list of luggage and things for the journey. Weimar: Ligne, Fragment sur Casanova.]

22.) 1796 June? (K 860) Dux -Wien - Dux. This journey mentioned by Meissner (information by Helmut Watzlawick). Presumebly he met his brother Francesco when painting the famous portrait.

23.) 1796 September (K 150) Dux - Dresden - Dux. He met his old friend Antonio della Croce, and Montevecchio [Marr 8-102: Teresa Casanova's letter of 8th September 1796].

24.) 1797 March/April (K 370) Dux - Prague - Dresden - Dux. In Prague he met Meissner's grandfather. In Dresden print of "Lettre à Léonard Snetlage".

[Bold print and annotations between [ ] are my own.]Thomas Nugent: Manners of Travelling.

Excerpts from "The Grand Tour", London, 1749, 1756 and 1772.