THE CASANOVA TOUR

by Pablo Günther

TRAVELLING CARRIAGES (part III , IV - VIII) - The English Coupé or Post Chariot - From Casanova to Napoleon I. - Transportation of Dismantled Travelling Carriages - Napoleon's Waterloo-Post Chaise - A History of the English Coupé in the Eighteenth Century. (Part VI: Casanova's Carriages)

Englishmen called it "Post-Chaise" or "Post-Chariot", Germans "Englischer (Reise-) Wagen", Frenchmen "diligence à l'anglaise", and Casanova said "voiture anglaise", English carriage. I call it English Coupé, because it was a coupé, and it was an ingenious English invention.The English Coupé or Post Chariot. From Casanova to Napoleon I.

"Riche Diligence de Ville Montée sur des Ressorts à l'Angloise". Design by Chopard, Paris, about 1775. The view of the body on the left side shows a typical feature of the English Coupé: the two front windows. - Photo: Museum Achse, Rad und Wagen, Wiehl.

In the USA, thanks to the Goodwin Report, things are better: the author collected in Virginia sixty-one references to the English Travelling Chariot and ninety-five to the English Town Chariot (which was practically the same type of carriage) of the time between 1757 and 1799. There, and in some other colonial and later U.S. countries, some famous owners were:In Europe, it is mostly the famous owners whom we know about:

Martha Custis, when marryingGeorge Washington (Treue,p.287ff.) in 1759, owned a Chariot. In 1768, Washington ordered a new one from London (the first President of the USA owned between 1750 and his death in 1799 "only" thirteen travelling and town carriages, while Casanova owned altogether nineteen).

Thomas Jefferson (Goodwin,p.lxx), third President of the USA, paid carriage taxes in 1773 for a Chariot. In 1788 he ordered a further one from London for 171 Pounds Sterling (41,040 d.).

John Brown of Providence, Rhode Island, ordered from Philadelphia in 1782/83 a still existant Post Chariot, in which he undertook great journeys.

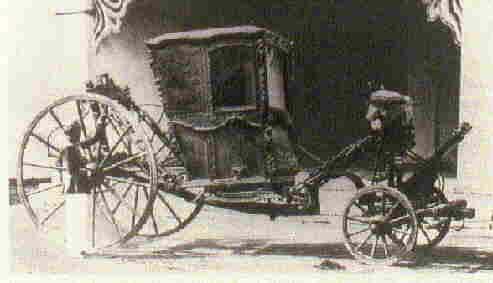

From the nineteenth century, I will mention only two famous owners out of the many thousands everywhere:The travelling chariot of Emperor Franz I of Austria. - Photo: PG.

Napoleon I lost, after the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815, his third military English Coupé, "the exterior of which is identical to the customary English travelling carriage" (Zeitung für die elegante Welt, Nr. 95, 1816).

Franz I of Austria travelled with a coupé very similar to that of Napoleon. It was built in Vienna by the Hofsattlerei around 1825, and still rests in the Wagenburg, the carriage museum in the chateau Schönbrunn.

The English Coupé can be distinguished by four basic types:I must state, however, that I have yet to find a picture of the English Coupé "GT". But for the present, let us enjoy Casanova's way of travelling through the Alps.

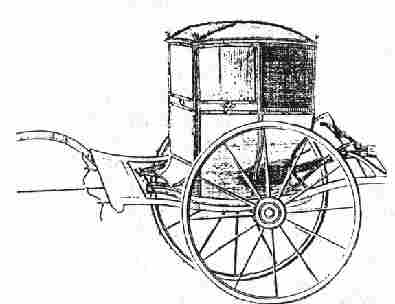

Type 1: The Post Chaise, as a simple travelling carriage (without coachman's seat), e.g. the "Lister Chaise" and "Felissent Coupé". Thomas Rowlandson shows the Post Chaise on dozens of his drawings in the first quarter of the 19th century. Undercarriage: always one perch. Body: always closed.

Type 2: The Post Chaise or Chariot, as a noble travelling carriage e.g. the "Compiègne" and the "Wythe Chariot". Another example is the War-Coupé of Napoleon I. Undercarriage: one or eventually two perches. Body: closed or convertible.

Casanova's Coupés "GT" belong to this category. Undercarriage: always one perch, easy to dismount from the axle-trees. Body: convertible, the upper part easy to dismount from the base.

Type 3: The Post Chariot, as a noble travelling and town carriage, e.g. the "John Brown". Undercarriage: usually two perches. Body: additional windows behind. In close relation is:

Type 4: The Post Chariot, as a pure town carriage, e.g. the "Diligence de Ville". In England it was also called Town- , Dress- or State-Chariot, and on the continent Berlin- or Gala-Coupé (from about 1800 onwards, the term Berlin refers to the shape of the body in English style and no more to the undercarriage with the typical two perches). Undercarriage: one or two perches.

Transportation of Dismantled Travelling Carriages.Between 1749 and 1763, Casanova crossed the Grand Saint Bernard once and the Mont Cenis five times, always with his English Coupés, and with each of the four that he possessed.

A Webley's convertible chariot, also called a Landaulet (London 1763), could be more easily dismantled than a coupé with a closed body. Thus I believe that Casanova's English Coupés "GT", suitable for the Grand Tour, looked like this. - Fitting-up and photo: PG.Travelling with English Coupés, Casanova says:(HL,vol.III,p.75) "We set out [with his English Coupé "Cesena"] from Parma at nightfall, and we stopped at Turin for only two hours to engage a manservant to wait on us as far as Geneva. The next day we ascended Mont Cenis in carried chairs, then descended to Lanslebourg by sledge. On the fifth day we reached Geneva and put up at the 'Scales'."

(HL,vol.III,p.77) "The next day I set out [with his English Coupé "Geneva 1"] for Italy with a servant whom Monsieur Tronchin gave me. Despite the unfavourable season, I took the route through the [Grand] Saint Bernard, which I crossed in three days on the seven mules required for ourselves, my trunk, and the carriage intended for my beloved [Henriette]. (...). I felt neither hunger nor thirst nor the cold which froze all nature in that terrible part of the Alps."

(HL,vol.VII,p.283) "After obtaining a letter of credit on Augsburg I left, and the next day I crossed the Mont Cenis on mules - I, Costa, Leduc, and my carriage [his English Coupé "Pisa"]. Three days later I reached Chambéry, putting up at the only inn, where all travellers are obliged to lodge."

(HL,vol.IX,p.33) "My felucca, which was of good size, had twelve rowers and was armed with some small cannon and with twenty-four muskets, so that we should be able to defend ourselves against pirates. [My servant] Clairmont had cleverly had my carriage [his English Coupé "Geneva 2"] and my luggage arranged in such a way that five mattresses were stretched across them at full length, so that we could have slept and even undressed as if in a room. We had good pillows and wide covers. A long tent of serge covered the whole ship, and two lanterns hung from the two ends of the long beam which held up the tent. - (P.40) At four o'clock we were off Nice, and at six o'clock we landed at Antibes. Clairmont saw to having everything I had brought in the felucca taken to my rooms, waiting until the next day to have my carriage made ready for the road again ["faire remonter"]."

1. Method "Grand Saint Bernard": possible use of sledges:What can other travellers tell us about crossing mountain passes with their own carriages? Again, it is the Mont Cenis, the classical pass of the Grand Tour, of which some travellers have left a description.

For the passage, Casanova had at his disposal 4 mules which transported the Coupé. This they could have done as follows:

The body was

a) attached to two poles (like a sedan chair) and carried by 2 mules; or

b) put on a sledge (when there was snow) and drawn by 1 mule.

For the undercarriage the remaining 2 or 3 mules had to carry the following separate parts:

1) the four wheels;

2) the perch;

3) the rear axle-tree with the spring-transom;

4) the fore axle-tree;

5) the fore spring-transom;

6) the coachman's seat.

7) the pole.

2. Method "Mont Cenis": the use of poles and sledges was not possible on the eastern side of the pass:

Presumably at least 5 mules were needed.

The body was taken to pieces and transported by 3 mules:

the first mule carried:

1) the 2 doors (windows and blinds let down);

2) the frame of the front windows (without glasses and blinds which were let down into

the body-base);

the second mule carried:

3) the folding top;

the third mule carried:

4) the body-base (including the bench and the folding seat).

The separate parts of the undercarriage were carried by at least 2 mules.

"Some Italians, who pass often over the mountains, build the body of their coach as light as possible, and of such a structure that it may separated into two parts, by which contrivance they transport it on the cheapest terms. Englishmen, who take their own coaches, should provide such a carriage as may be taken to pieces, which those with a perch do not admit of."If I understand the last sentence correctly, English carriages with a perch, i.e. four-wheeled carriages, as a rule could not be taken to pieces, but Englishmen could purchase (special) carriages with this option in their own country.

Though no special type or model of an English travelling carriage (like the "GT") is mentioned, it seems clear that they usually could be taken to pieces, if the cartwrights or manservants had the special tools. The imperial or top had to be "very light", presumably for easier dismounting and transportation; light upper parts of the body could not be made of wood, but instead were made of cloth and some thin iron bars (like those of a Landaulet respectively Casanova's Coupés "GT")."Of things most requisite" "Those persons who design to travel much in Italy should provide themselves with a strong, low-hung crane-necked English carriage[this was usually a Post Chariot], with well-seasoned corded springs, sous-soupentes, and iron axle-trees; strong wheels, properly corded for travelling; two drag-chains (the one with an iron shoe, the other with a hook); two drag-staffs; a box, containing extra linch-pins, nails, and tools for repairing, mounting, and dismounting a carriage (this box should be made in the shape of a trunk, padlocked, and slung to the iron work of the carriage); a well; a sword-case; a very light imperial [top]; two moderate-sized trunks, the larger to go before, with a padlock and chain for the smaller; lamps, and a stock of candles fitted to them. The bottom of the carriage should be pitched on the out-side. A second-hand carriage, in good condition, is preferable to a new one; and an out-side seat, for a man-servant, not suspended on the springs, but fixed to the boot, and slung upon leathers, may frequently prove useful. Every travelling - carriage should be made to lock up; and the boxes of the wheels should be brass."

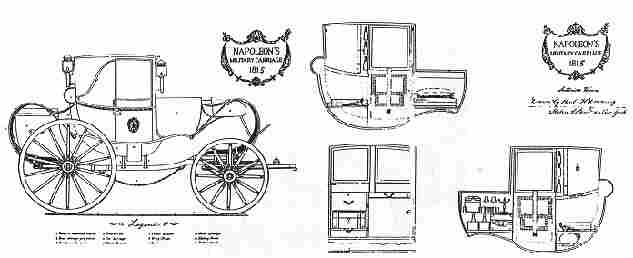

Napoleon's Waterloo - Post Chaise.An English Coupé which achieved the highest possible distinction and, in its time, great celebrity, was the last of three known military post chariots of Napoleon I.

According to the researches of Max Terrier, the Emperor "had three different equipages with the army":For the campaign of Russia, Napoleon's favourite supplier, the (English?) coachmaker Getting in Paris, delivered to him a Post Chaise (No. 300 of the Imperial Mews) on March 5th, 1812. It returned from Moscow without him and, in 1814, was taken by his wife Marie Louise to Vienna, together with twenty-five other carriages.

1. His armoured Post Chaise, officially called "voiture de poste" (or "dormeuse", sleeping carriage; Napoleon used to say "chaise de poste"), a widely equipped military carriage;

2. His Calash "de service leger", from 1812 onwards a Landau à l'anglaise (the Waterloo - Landau: today in the museum of Malmaison, Paris);

3. His string of riding horses.

The Post Chaise No. 336 during the campaign in the winter of 1813/14. A realistic view of the carriage. The shape of the body did not change in principle from those of Casanova's times. - Lithography by R. Desvarreux. Carriage museum of Robert Sallmann, Amrisvil / Switzerland. Photo: PG.

Napoleon's last Post Chaise (No. 389 "Waterloo") in the museum of Madame Tussaud, London. - Photo: Terrier / Tussaud.

"To the Copper No. 4." "Our readers get here a picture of the carriage of Bonaparte which was captured by the Prussian troops in the battle near Waterloo and presently is in London where it is on show to the public. The exterior of this is equal to the customary English travelling carriages. The colour is of a dark blue and the bordering makes a beautiful golden arabesque. On the doors are the Imperial arms. On every corner is fixed a lanterne, and another at the rear side which gives a heavy light into the interior. In front, there is a large projection, and then follows the coachman's seat which is placed so as to prevent the driver from viewing the interior of the carriage. The sides of the carriage are armoured against balls. The undercarriage is very durable, the wheels and the pole especially are very firm. All this is painted red and ornamented by gold. The body is suspended in such a way as to not easily loose balance even on the worst roads. The interior can be arranged for different uses. It can be used as a bedroom, dressing-room, dining-room or kitchen, &c. The seat has a partition, perhaps out of pride, perhaps for comfort. Receptacles for utensils of all kinds everywhere are installed. Newspapers are already aquainted with the items in these receptacles. Beneath the coachman's seat there is a small receptacle containing a bedstead of polished steel; other necessities for a bed were found in the carriage itself *. In addition, a writing-desk is attached which can be pulled out so that one is able to write even while the carriage moves on. Likewise, for maps, telescopes &c, there are cases everywhere. On one door you see pistol-halters in which there were loaded pistols from the factory at Versailles. The inward door windows are supplied with blinds which can be drawn up by springs, forming then with the sides of the carriage an impenetrable wall. The front windows are protected in a similar way, too. The horses on the carriage were of Norman race and brown colour, and rather strong and fiery."

------

[* Captain Malel: "The exterior of this ingenious vehicle is of the form and dimensions of our large English travelling chariot, except that it has a projection in front of about two feet, the right-hand half of which is open on the inside to receive the feet, thus forming a bed, while the left-hand half contained a store of various useful things."]

A History of the English Coupé in the Eighteenth Century.At least four of the seven coupés owned by Casanova were English Post Chariots. In Great Britain this type of vehicle - also called Post Chaise - was the most usual and agreeable travelling carriage, and on the continent, the most noble. How it arose and developed in the course of the 18th century is briefly outlined as follows. In addition, I would like to list all the extant English Coupés that I have come across in my research.

2

2  3

3

It seems at first that the coachmakers experimented with the relatively new undercarriage of the Berlin. There is a drawing, which I date around 1740, which refers to this (picture 4; photo: PG, from the original of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London). The horizontal fixed steel springs soon ceased to be used. Most remarkable, however, was the new coupé-body, and for the first time we see the clear and symmetrical lines which became "typically English" for the whole future age of coach-building. The sides were straight and not vaulted nor richly decorated as they usually were in France. The rear side was still in the manner of the Carosse-body but the fore side was drawn more forward than was usual in later years. The rear upper part of the body and the roof could be folded back, thus the body was a convertible, also called a Landaulet.4

1749, July: Casanova bought his first Post Chariot from Count Dandini in Cesena.

1750, January: He obtained the second, from Henriette in Geneva.

6

6

Differing from opinion in England which dates the Lister Chaise 1740 or before, I believe it to be of a later construction. It is identical in design to the Post-Chaises of Webley in 1763 (see next picture) and appears for the first time in an inventory of 1766, which gives it a value of only 20 Pounds Sterling. Because we know the prices of new Coupés (cf Casanova, Felton, and others) were about 120 Pounds Sterling at that time, the Lister Chaise must have been at least ten years old when valued in 1766.7

1760, November: Casanova bought his third Post Chariot from an Englishman in Pisa.In 1763 the London coachmaker, A Webley, published his catalogue of carriages with, among others, "Post-Chariots" and "Post-Chaises", very realistically designed as we know by comparison with the Lister Chaise (picture 8; a chaise like the Lister; photo: PG).

1762, August: Purchase of his fourth one, in Geneva.8

Two drawings by Paul Sandby made in 1763 (pictures 9 and 10; photos: Windsor Castle, Royal Library). Neither Chariot has a coachman's seat: thus we have other drawings of a Post Chaise as we know it, as distinct from the Coupé with a coachman's seat, called a Post Chariot. The carriage in picture 9 is the older model to judge by the curvature of the rear side of the body (carosse-style) and by the rear suspension, which consists of two straps of leather connected above by short spiral springs to the wooden pillars. At the front, however, steel springs were mounted in the shape of so called whip springs, similar to the other carriage (10), where we find these springs also at the back.9 10

1764, May: Casanova purchased from General John Beckwith of London, stationed in Wesel, Germany, an (English?) Coupé.

1766, July: Count Mosna-Mosczynski in Warsaw, presented Casanova with one of his own (English?) Coupés.

In 1768, the Oxford Magazine showed the coupé of the Prince of Mecklenburg - Strelitz (picture 11; photo: PG, from an original print in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London), a carriage similar to a Post Chariot: a Town- or Dress-Chariot, with a berlin undercarriage. These town coupés also had a front window divided in two parts; an arrangement originally for travelling which became extended to carriages for ceremonial use.11

By the end of the 1760s, the English Coupé was causing a sensation in that other great centre of coachbuilding, Paris. The coachmaker and author André Jacques Roubo rejected it as inelegant and without style, but he had to agree to its efficient driving qualities. Here are some excerpts from his book published in 1771 (the bold print is my own):* * * * * * * *

" (...) they are less rounded and less high than ours [post chariots] (...) they do not have any windows at the rear side, and no curved struts, and the front window is customarily divided into two parts, which can be let down independently from each other (...) The carriages à l'Anglaise are presently very up-to-date and I really do not know why, for they have neither a beautiful shape nor any grace, looking more like a box with several holes than a body; but it is enough that the invention of these carriages comes to us from England, in order that everyone has one or likes to have one, as if there was any law obliging ourselves to be servile imitators of a nation lying in competition with us (...) These carriages (...) seem to be in use only in the countryside, considering their great lightness and little height, which make them less susceptible to knocks from the side than the others. The perches of these carriages are always curved [compass perch], whether simple or double, which forces [the body] to be hung on springs, and that increases the smoothness [of the ride]."A comparison with the French Coupé (picture 12) shows to what Roubo's remarks refer. In those years, in Paris, at the beginning of the seventies, many designs of the Diligence à l'Anglaise were disseminated, among others by Chopard and Poilly. I found a couple of unpublished engravings in the Musée de la Voiture and Tourisme in Compiègne (picture 13: N.J.B. de Poilly, Diligence Angloise coupée ou Birouche; photo: PG).12 13

At this time (1770), Bernardo Bellotto was in Warsaw producing numerous vedute of that town, in which are illustrated, besides continental Berlin-Coupés and other vehicles, many English Coupés.* * * * * * * *

1770, September: Casanova bought in Salerno a "beautiful and convenient (English?) Coupé", which he finally sold in Bologna in October 1772.In 1774 another series of carriage designs was published in London: The "Currus Civilis" by Isaac Taylor. His Post Chaise (picture 14; photo: Paul H Downing) shows scarcely an alteration compared with the designs of Webley eleven years earlier.14

Of the same "older" style is the Diligence à l'Anglaise which can be admired in the entrance hall of the Musée de la Voiture et du Tourisme in Compiègne (picture 15; photo: PG). There the body can be dated "about 1775" though the determination of the two-perched undercarriage is more problematic; it could be somewhat earlier. However, seven years later the origin of a practically identical undercarriage for the next Coupé can be identified for certain.15

The John Brown Chariot (picture 16; photo: The Carriage Journal, Vol.5, No.2, 1967) was built by Quarrier & Hunter, Philadelphia, and delivered on 6th April 1783 to John Brown who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Today the chariot belongs to the Rhode Island Historical Society in Providence. The similarity with the coupé in Compiègne is great, except that it has two windows at the rear, which are typical for town-coupés. Also, the highly-suspended body is notable, which no doubt was useful for crossing creeks and rivers; although by then it might simply have become the fashion. Certainly from that time the coachbodies tended to be hung higher, though they could be lowered if required. The subsequent history of the John Brown Chariot shows that it was used for town as well as for long journeys.16

[1783, November: the brothers Giacomo and Francesco Casanova bought in Paris a travelling coach for their trip to Vienna; the carriage seemed to be extraordinarily good (judging by Giacomo's description in a letter), hence it could well have been an English one.]Highly-suspended bodies are found in almost all pictures of carriages in the fundamental book "A Treatise on Carriages" by the London coachmaker, William Felton, published 1794 - 1796; the convertible Landaulet (picture 17; photo: Paul H Downing) is a good example.17

In Italy, I had the luck to find another surviving Post Chariot: the Felissent Coupé of the Museo delle Carrozze, Villa Manin, Passariano, near Codroipo / Friuli (pictures 18 & 19; photos: PG). It is dated 1795 which agrees with Felton's plans of construction. Here we find for the first time C-springs, which although shown by Webley in 1763, nevertheless were seldom used in reality, in comparison with F- and S- springs (cf "Steel Springs"). In 19th century, however, C- springs became the usual type as illustrated in pictures 24, 25 and 26.18 . . 19

* * * * 19th century * * * *

From the beginning of the 19th century the English Coupé became most widely known. Thomas Rowlandson shows the simple Post Chaise on dozens of his drawings (picture 20; "The White Hart Inn, Bagshot"; photo by PG from: J. Jobé, p.98).20

An early State Chariot with Cee-springs was that belonging to Count Magnus Fredric Brahe, used in 1811 in Paris. Berlin-undercarriage with crane-necks. Today in the Livrustkammaren, Stromsholm, Sweden (picture 21; photo: Bernd Eggersglüß).21

To this type also belongs a beautiful chariot, which was delivered in 1812 to the General-Governor of Java, Stamford Raffles. It was built by T. Muers, London, (pictures 22 and 23; photos: Achse, Rad und Wagen, No. 1, 1991). The photo taken during renovation (picture 22) shows the construction of the body.22 . . 23

The Wythe Chariot, a post chaise of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in Virginia, dated 1820, still has the approved S-springs (picture 24; photo: Paul H Downing). Like the carriage of 1740, it is a "half" Landaulet (cf picture 4), that is, only the rear part of the body could be folded back.24

As another example of an early 19th century Coupé, shown is the noble Travelling Chariot of the Baskerville of Clyro in Powys (picture 25; photo: Wollaton Park Industrial Museum, Nottingham).25

An English Coupé, made in Germany (Friedrich Braun, Wagenfabricant, Hessen Cassel). Ordered by Prince Emil zu Bentheim-Tecklenburg (Westphalia) in about 1825 (picture 26; photo: Bentheim - Tecklenburg).26

* * * * 20th century * * * *

The history of the English Coupé did not end in the 19th century. The Rolls Royce of 1909 (picture 27; National Science Museum, London; photo: PG) belongs to the first generation of motorcars with a closed body. However, not just any coach body was taken but that of the English Coupé, with two front windows and other characteristics. The driver still had to sit in the open air like the coachmen.27

The front window, divided into two parts, continued as an element of design in building automobiles: e.g. a Jaguar sportcoupé XK 140 (picture 28; photo: ADAC Motorwelt 8/93) during the Mille Miglia for oldtimers from Brescia to Rome in 1993.28