Casanova between Venice and Dux (1782-1785)

1782 - 1783 - 1784 - 1785 . . . An overview of his travels in this period: Table of Casanova's journeys Vby

Marco Leeflang

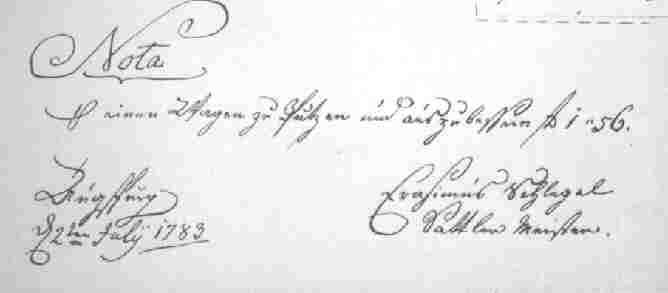

Pictures: (above left:)

Giacomo Casanova, by Pietro Longhi - (above right:) Giacomo Casanova,

by Francesco Casanova -

Prince

de Ligne - Oldest car wash-bill in

the world - Francesco

Casanova - Giovanni Casanova, by A

Raphael Mengs -

Poststation

in Italy, by Francesco Casanova -

For the second time Trieste became Casanova’s jumping-off point. In 1774 he waited here for permission to return to the Serenissima. Now, in 1782, he is preparing for his final departure from Venice. He judged it was of no use waiting for the dust to settle from the storm he had raised with his publication, Neither Loves Nor Ladies (Nè amori nè donne). Undoubtedly his prior experience with the conservative government, which had cost him an 18-year exile, had made him cautious.1782

Venice in those days was more or less a police state. Secret trials were common. Crackdowns followed where modernization was proposed. Traveling was prohibited for the nobility unless specific permission was granted. Freemasons were a horror: their possessions were burned and their leaders banned. Freedom of press and speech were not a right but dangerous.

Casanova had friends among the nobility with more liberal views, like Andrea Memmo and Pietro Zaguri, but that was no safeguard. The fate of the unfortunate Lorenzo Da Ponte, a protégé of Memmo and Zaguri, was a recent example from Casanova’s inner circle. In 1779 Da Ponte was banned for 15 years.

In a publication, Da Ponte had posed the question "whether man wouldn’t be happier in nature than in society." This was considered blasphemy. And when his social conduct too surpassed the limits of acceptability(1) (the 30-year-old abbé had a child with young Angioletta Bellaudi and had brought it himself, in soutane, to the foundling home), he fled the country before the authorities could get hold of him. Casanova would meet him again later when Da Ponte had managed to become poet of the Austrian Theatre and was writing libretti for some successful operas of Salieri and Mozart.

Casanova’s decision to leave Venice had been triggered by the written advice of the procurator of St. Mark’s, Francesco II Morosini, a friend from old times and now in high office in Venice. The procurator had sent a letter poste restante and a messenger advising Casanova to pick it up. In the meanwhile Morosini apparently had been able to calm the waters of the turmoil by stopping the circulation of Neither Loves Nor Ladies, which, by the way, had received the official approval of the censors. The whole edition was confiscated. On August 31, 1782, a Mr. Ballarini wrote to the Venetian ambassador in Paris the news that "the booklets were rigorously collected." The terms in which Morosini had written to Casanova sounded rather harmless—"It would please me not to encounter you in Venice for some time"—but he also advised him to leave the country as soon as possible. In reply (2) to this letter Casanova complains about the harshness of Morosini but says at the same time that he should have left the country two years earlier. Then he strikes the word "two" and replaces it with "three." "During the last three years I lived in Venice in a continuous state of violence, I should have decided earlier to go and live elsewhere." Again his pen crosses out a word. To "live elsewhere" is not dramatic enough—to "die elsewhere" sounds better. And as his honor is hurt by being urged to leave immediately, he stresses he will present himself "next Thursday or Friday morning at the front door" of Morosini’s palace. Besides, before departing he will have to wait for answers on his letters to his family in Paris and Dresden, and he has to arrange something for his nephew Carlo, the son of Giovanni Casanova, who temporarily lives with him. He cannot possibly settle his affairs before October 22. The future looks gloomy. "I am 58 years old; I can’t travel on foot; winter is coming; and when I think of becoming an adventurer again, I start laughing when I look in a mirror."

The Memoirs cannot help us for the next 16 years of Casanova’s life. On the one hand this is an enormous disadvantage, and we will miss many details, but on the other hand we now have some rather reliable data which have not been edited and reedited in order to adjust to his literary aspirations. The reports from others and the notes and drafts of letters which are preserved among Casanova’s papers, like the Morosini letter just cited, are more straightforward than the Memoirs. This legacy is plentiful. Some 800 items date from before Casanova’s final departure from Venice in early 1783, and some 1,250 can be dated from the subsequent 16 years.

Joseph II had become emperor in 1780 and had

started modernizing many things that had been taken for granted. Among

the big issues he was working on were religious toleration, emancipation

of the Jews, abolishment of serfdom, church reform, land tax reform, and

social legislation. But there were also smaller adjustments. One of those

was that Joseph II was easily accessible and welcomed meeting the people,

including foreigners. And one of those was Casanova.

Prince Charles de Ligne [picture:

painting in Teplitz Castle. Photo: P. Günther] relates in his

Fragment

sur Casanova, frère du fameux peintre de ce nom(3)

an encounter between Joseph II and Casanova:

"Yes," Casanova replied, "a Venitian nobleman."

"I don’t like his type of nobility so much. I don’t esteem those who buy it."

"And what do you think of those who sell it?"

Casanova renewed acquaintance with Da Ponte who, in 1782, after the death of Metastasio, poet of the Imperial Theatres, posed as a candidate for the vacancy. And when Salieri recommended Da Ponte to Count Rosenberg-Orsini, the director of Performances, he got the job, though not the title of "Imperial Poet," because Joseph decided to discontinue that title.

Casanova probably met again with Prince Kaunitz-Rittberg, the longtime chancellor of Austria, whom he knew from his last visit to Vienna. There is no record of their meeting in this period, but the ease with which Giacomo’s painter-brother Francesco Casanova obtained Kaunitz’s protection later in 1783 points in that direction.

He also met the abbé Eusebio Della Lena (1747-1818), bibliophile, man of letters, who earlier had owned a bookstore in Venice but who was now rector of the Theresianum. It is to him that Casanova addressed a letter which sums up what happened between June, when he left Vienna for a short and last visit to Venice, and September 1783. This letter was first known in a shorter version, maybe taken from a draft by Casanova, but the original (4) has been found among the treasures of Brockhaus, the German firm which still owns the manuscript of l’Histoire de ma vie. It is worth reading it in full, and we will interlard it with clippings from the letters of Francesca Buschini,(5) the girlfriend Casanova left behind in the Barbaria delle Tolle near the statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni. Her comments too are most valuable in tracing Casanova’s whereabouts, because in her letters she always echoes the news he wrote to her.

Here is Casanova’s letter, punctuated with details from Francesca’s:

You know already that I spent a week in Udine at the home of the lieutenant [of Friuli, Carlo Antonio Donà] where I had the honor of dining with Nicolò Foscarini [former ambassador of Venice in Austria]. From there I went to Venice [about June 14, 1783], where I was pleased to go nowhere but to my home and then to Mestre with the whole family which I support in my house [Francesca Buschini, her mother, her sister Maria, and her brother Giovanni] and who are the only people I care for in my country, which is too indifferent toward me. Three days later I left Mestre, and I went to Basano to look up Father Boscowitz

. . . [Roger Joseph Boscowitz, Jesuit, mathematician, and astronomer, who stayed in Bassano for the supervision of the printing of his works].

So you have embarked on the Rhine together with the Marquis Durazzo whom you had met in Mainz, and you have arrived two days later in Cologne. Your assurance that you have an iron health, sleep well, and eat only once a day as a wolf has comforted me, only from the last two letters I gather that you are less well, that you have no appetite, and that you don’t sleep well, but I believe it is due to the baths. I hope you are better now. In your second letter from Spa, July 23, you complain not to have received a letter from me

. . . . For the third letter from Spa, July 30, which I received August 10, I thank you very much for the sweet thought of inserting a golden coin . . . .

There is a note (7), written by Casanova in Spa, which illustrates his uncertainty and the diversity of his thoughts. It lists:

Confidential information [by whom?] of the suitcase [whose?] left in Frankfurt for 20 louis.

Need a suit and have to go to Paris.

Recommendations for Paris.

Confidential information of the project of Madagascar.

Advice about the stock shares of Volf [?].

Project for a canal in order to avoid the Strait of Gibraltar.

Coach left behind in Mainz at Rossi’s.

Canal which crosses France from Narbonne near Carcassonne, via Pau to Bayonne.

One of the oustanding Casanovists, Helmut Watzlawick,(8) has solved at least one of these mysteries: that of the Madagascar plan which seems to come out of the blue, but doesn’t.

While studying the List (9) of people who have come to the mineral waters of Spa, where on July 26, 1783, the presence of "Monsieur Casanova, Gentilhomme Vénitien à l’Hotel du Louvre, rue d’entre les ponts" is stated, he found the name of Count Maurice Augustus Benyowsky, whose arrival in Spa was announced on July 19th.

This count, born in 1741 in Hungary, led a life full of adventure in Poland, Russia, Alaska, Japan, Formosa, and other places. Arriving in France in 1772 he presented a plan to establish a French colony in Madagascar. He succeeded in mounting an expedition, which was realized but which encountered all sorts of trouble, and he returned to France in 1777. In 1782 Benyowsky submitted new plans to the French minister of Foreign Affairs; when he received no immediate reply he traveled to Vienna where he solicited and was granted the sponsorship of Joseph II for a colony in Madagascar under the imperial flag, but without financial backing. In November 1783 Benyowsky’s presence was signaled in London, where he tried to get British support for his plans. But in vain. Finally he succeeded in Baltimore, and in October 1784 the expedition left but encountered many mishaps.

No doubt Casanova met Benyowsky in Spa on his way from Vienna to Paris and considered joining the expedition. That solves one mystery.

The English lady remains a problem. The same List of visitors might help, and indeed there is a "Madame Thomson, dame anglaise" and a "Madame la comtesse Dalton, avec mlle Plunkett." However, although they are the only women without a man’s company, there is, as yet, no concrete evidence that either was Casanova’s famous "dame anglaise."

A last look at Spa’s List sheds light on the background of a poem Casanova published on August 19, 1783: his Vers publiés a Spa, (10) signed by "a poet drifting from shore to shore, sad toy of the waves, and driftwood of a wreck," and honoring a "great warrior who invited the whole nobility [including Casanova!] for a grand déjeûner in Spa’s Vauxhall."

The List identifies the warrior as Charles Henri Nicholas, prince of Nassau-Siegen (1745-1808), known as the inventor of floating batteries during the Spanish-English war. Named Spanish major-general, he joined, after the peace in 1783 (and after some leisure and party time in Spa), the Russian service as vice-admiral, defeated a Turkish fleet in 1788, and also had successes in the sea war against Sweden. François Casanova made several portraits of the prince, but it is not certain whether it was François or Giacomo who first became acqainted with him.

But let us continue with Casanova on his journey

from Brussels to Paris. He had planned to visit in Brussels Count Lodovico

Antonio Belgiojoso-Este, the Austrian major-general who was vice governor

of "Belgium" and nicknamed Belgiodioso because he was so hated. This visit

either never took place or led to no result. After all, lotteries were

not as novel in the 1780s as they had been in the 1750s and sixties. Casanova

cashed the check of 25 guineas, and to Francesca he sent 150 lire—which

then paid for eight months rent—continuing to write her once a week.

Giacomo makes an inventory of the situation. Debts in abundance. A survey is made: (13) Mr. du Frenois has promised to diminish the personal debt of Francesco by one third. It was 31,716 livres, so 21,144 livres remain. Therefore Francesco must lower the price for two large framed paintings by 7,000 livres. [. . .] After the death of Mr. Poulain, his mother found loans to Francesco in the amount of 17,000 livres. In lieu of payment of this sum, she demands that Mr. Casanova make four large paintings, two to be delivered in 1784 and the other two in 1785. [. . .] Plus 6,000 to Mr. Bourgeois de Cretienville, 5,600 to the handworkers of Franconville, 1,200 to the watchmaker, 2,300 for the paint merchant, 1,200 for the hatmaker . . . . Furthermore, if Francesco would like to retrieve his pawned possessions, another 4,000 is needed. And there are undoubtedly other creditors.

On the income side, the job is to sell paintings and obtain new orders. Giacomo serves as sales manager. Together with Francesco he looks over the situation and makes another list (14):

To the Duke of Crillon who lives in St.Clou, and for his address in Paris, I’ll ask the Duke of Aranda, rue neuve des Petits Champs. I will report to Crillon the conversation with the Viscount Hereira about paintings for the Prince of Asturia; that two large and beautiful ones are finished, the need to hurry, the wish to serve him by painting the two things in question about which the duke has spoken.

To the Viscount Hereira, Spanish ambassador to Sicily (have to ask where he lives) try to get commission of four paintings for the Prince of Asturia, inform him a bit of the present situation.

To Intendant Berthier. He lives next to the intendance, rue Vendome in the Marais near the rue Saint Louis; tell him everything and ask him to take care of the administration, and even offer a security in some way or another, that without that Francesco is left to the discretion of cruel creditors and a hostile wife. Offer him available paintings, either battles or landscapes.

To Girardeau de Marigni, banker in the rue Vivienne. No word about the present distress. Tell him only that if he wants to have the two battles, he must hurry because time presses. His wish to add paintings by Francesco to his collection. That Francesco hopes he will come to have a look.

To Mr. de Beaujon at Hôtel d’Evreux, rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré. Tell him everything in order to make him buy the paintings. Flatter him a lot. That in Vienna I have heard talk about his gallery.

To Mr. de Tot, rue de Varenne at Hôtel de Tessé at the queens stables. A letter of recommendation etc.

The 3,000 livres no doubt were, at least in part, used to finance the trip to Vienna and not to satisfy Francesco’s creditors.

One of the few, perhaps, who managed to control the damage was the butcher Fiquet, who had a brother living in Vienna as a dance master. (16) This brother made a deal with Francesco: "If you let me have one of your paintings, my brother will forget about his unpaid bill for meat."

In a letter dated November 11, Casanova writes to Francesca advising her to hold her letters because he does not know what the future brings.

On November 13, the Venetian ambassador to Paris, Dolfin, issued a passport to the two brothers (17) and said he was sorry Casanova left Paris so soon. He also mentions a legendary inheritance of 200 million francs left behind by Giovanni Thierry d’Hagenau at his death in 1676. He assures Casanova that this treasure "doesn’t exist and never has existed." Would this perhaps have to do with the above-mentioned "shares of Volf"?

At the same time the other painter-brother, Giovanni Casanova [photo]

in Dresden, had comparable troubles. He was a widower since 1772, was no

great bookkeeper either, and borrowed money wherever he could. One of his

creditors was the stepmother of the painter Raphael Mengs. Mrs. Katherine

Mengs-Nitscher, second wife and widow of Ismaël Mengs, insisted on

marrying Giovanni in order to have some security for her loans. Giovanni

had to defend himself in court to keep her at a distance(18).

At the same time the other painter-brother, Giovanni Casanova [photo]

in Dresden, had comparable troubles. He was a widower since 1772, was no

great bookkeeper either, and borrowed money wherever he could. One of his

creditors was the stepmother of the painter Raphael Mengs. Mrs. Katherine

Mengs-Nitscher, second wife and widow of Ismaël Mengs, insisted on

marrying Giovanni in order to have some security for her loans. Giovanni

had to defend himself in court to keep her at a distance(18).

Of course Giacomo did not spend all his time on the affairs of Francesco. He also tried to find a means of living for himself and intended to start a periodical, as he had done in Venice. Francesca echoes from Venice: "You tell me you do nothing but write and that you have the intention to publish a journal; so I wish that this newspaper finds response and that it will yield you some money(19)." It probably was Il Telescopio di Cecco Curione, but this project seems not to have reached a status more advanced than a prospectus(20).

Many old acquaintances had died, and maybe that had its advantages too because, as in Vienna, his last departure from Paris had not been voluntary. The fact that he was not arrested in 1783 will even be used later by Casanova as proof that the arrest of Parliament and the lettre de cachet of 1769 had no power anymore(21).

Anyway he felt free to attend a meeting of the "Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres," in November 1783, where he was seated:

We next hear of the two Casanova brothers when they arrive in Frankfurt at the Hotel L’Empereur, where the host of another hotel, Au Raisin d’or in Augsburg, Johann Maijr, quickly sends a note, dated November 26, to remind Giacomo of his unpaid hotel bill of five months earlier (23).

A letter sent the 26th to Mainz asking information about the sale of the coach he left there in August is answered in the negative. Even for six louis d’or there is no buyer, and it is agreed the coach be sent to Frankfurt by a carrier who charges three florins and 12 creitzers. "We are sure you will have received it safely, and in Frankfurt you will more quickly find an interested foreign buyer, because many strangers are traveling through there and could be seeking a similar chaise(24)."

The trip from Paris had not been without complications, as echoed by Francesca (25): "I received a brief letter from you, which you wrote to me on the 29th November from Frankfurt, and from which I learned to my great sorrow and regret that the drunken postilion had overturned you and that the fall had dislocated your left shoulder, but a good physician was able to put it back in place again . . . ."

On December 1st he assures Francesca that his arm is in order again, that he has taken medicine, and that he has been bled. In addition, he lets her know that in one month he will send her eight zecchini, with which she can pay the rent and use the rest for any necessities.

As promised, Casanova sends his next letter to Della Lena, looking back at his last days in Paris and stating his plans for the near future:

Signor Abbate, my very dear sir and revered friend,

Two weeks ago your friend in Paris sent one of his dear friends to my house; I ran immediately to him as I had a great desire to know him because of what Bartoli [ perhaps Giuseppe Bartoli born in Padua in 1717, archeologist of the king of Sardinia, member of the Academy in Paris, professor at the University of Padua and later in Turin] had said about him, but I could only stay a few minutes because it was precisely the day of the return of the Academy of Science, at which assembly the celebrated American Franklin had engaged me to attend. Then I had to go to Fontainebleau and on my return to finish a thousand trifling things before leaving Paris that took up my time, so that I could not return to enjoy the sound doctrines as much in mathematics as in Christian morals of your dear Signor Cagnoli, who did not break off his study of the stars except to compose the dispatches of two ambassadors.

The letter with which you honored me gave me much pleasure, particularly to know that his Excellency the ambassador had improved his precious health at those baths in Baden [near Vienna]. I shall come to enjoy some small influence from it, if his Excellency will permit me on the 8th or 9th of next month, and now through you the current month of December. You will forgive me if, trusting to your goodness, I venture now to entreat your kindness over a difficulty, which is not small, but which is infinitely within your powers.

I shall arrive within 10 or 12 days in Vienna with a dear companion [Francesco] to pass the winter and spring there, where I desire, not so much for reasons of economy as to avoid being cheated, to know where to lodge when we get out of our coach. I should like you to find me a decent lodging, either in the city or in some suburb, comprising two good-sized adjoining rooms and, if it is possible, that can be suitably heated by a single stove, because wood is expensive there. I should like these rooms to be light, both furnished with a good bed, a chest of drawers, two small tables and four or six chairs, and in addition, I should like to be able to put our closed coach, either in the house, or somewhere nearby, so that it does not remain exposed to the ravages of the weather, and to those of thieves. For the rent, you can make an agreement, and we will immediately pay a month in advance: I will agree up to the sum of six zecchini a month, and you can be sure we shall be happy with the agreement you make and shall be much obliged to you for it. Besides this, it would be wonderful if you could find us a servant, who as well as German also speaks Italian or French! If this servant knows how to dress hair, it would be better still, and if he could agree to a very small salary. I believe that in Vienna, it is easy to have our meals delivered, either from somewhere nearby or in the house, when we wish to dine at home. Now you will clearly realize that time is short and you will have to be kind enough to start searching immediately; and after you have reserved the apartment, you would have the goodness to write me a note in which I shall find the address written down, and I will order the postilion to take us there. This note should be sent direct to me at Burckendorff [Purckersdorff], which is the last post-station for those arriving in Vienna by the road from Ratisbona and Lintz. I should be pleased if the lodging is not very far from Vienna. I will say also on the advice of my companion, whom I know you will be pleased to meet, that if you should find a lodging that costs more, I authorize you to agree also to seven zecchini a month, and even a bit more, provided it appears to you that at least one of those rooms is fine and spacious.

When we see each other I will not speak about the English lady, but I will tell you why I refused to go to Madagascar, and you will approve. I desire to find peace, dear sir, and not to be buffeted anymore by fate, as I no longer have any of those ambitions that make a man chase after fame and fortune.

I beg you to convey my most humble respects to his Excellency the ambassador [Sebastiano Foscarini] and to his son Signor Giacomo, whom I hope to see at the riding school, trotting and galloping, having become very proficient at dressage, and furthermore I am sure I shall find him advanced in his studies.

We will chat about various things in Vienna after I have spent some days in the apartment there recovering from the fatigue of the journey, as I have done 400 [Italian] miles [600 km; in reality 660 km] from Paris to here in five days, and now in another five or six I will do 480 [720 km], which separate Vienna from Frankfurt, where it is bitterly cold. Bartoli is a great friend of yours and asked me to greet you. I only stayed two months in Paris, and I left despite the opinion of powerful gentlemen who wished to stop me, but I had good reasons. I shall be able to return there in the summer. I shall finish wearying you, assuring you that I long to embrace you, and to give you, with deeds more than words, true marks of the high esteem with which I have the honor to be . . . .(26)

He also announced plans to extend his trip toward Berlin, according to Francesca’s letter of December 1783: "I hear you will go to Dresden and then to Berlin and that you will return to Vienna on January 10th." And a letter from Obizzi, dated December 27th,(27) indicates the same: "I hope my letter will find you happily returned from Berlin."

It is not clear if Della Lena was willing and able to carry out the lodging orders for the oncoming brothers. Anyway, upon arriving in Vienna, Giacomo continued his trip and first went to see brother Giovanni in Dresden, where he arrived before the end of the year after an uncomfortable journey.

Francesca Buschini, January 14, 1784, Poste Restante at Vienna (28):

The Casanova brothers, Giacomo, Francesco, and Giovanni were quick-tempered and rather outspoken in their feelings against each other. There is no record they ever lived together in exemplary peace. Their sister Maria Maddalena, married to Peter August, clavecinist at the Dresden court, may have been the only one who formed a counterweight to the centripetal forces in the family. The fourth brother, Gaetano, a priest of whom Giacomo talks only in disdain, had died in 1783 in Rome, but it may well be the family hadn’t heard the news yet.

Giovanni had become one of the directors of the Academy of Art in Dresden and was well-esteemed. Unlike brother Francesco, who despised allegories and references to the Ancients ("I insist that painters should suppress all those gods who do not make a painting understandable for the people of today and for posterity (30)"), Giovanni loved them. He even wrote a book for his students, praising and explaining the old world of gods, myths, and allegory(31). He may have started to assemble and produce his collection of cameos during his apprenticeship in Rome, where he cooperated with (and cheated on) the famous archeologist Winckelmann. This collection was so important that in 1792, Catherine II of Russia, who was addicted to cameos, bought all 274 of them together with his handwritten catalogue(32).

What happened when the family met again in December 1783 remains misty, but there must have been a severe clash, for in a letter to Giovanni, written January 9th from Dessau, a few days after their meeting in Dresden, Giacomo proposed a reconciliation:

On January 9, Giacomo was in Dessau. He probably visited the Buchhandlung der Gelehrten to check out the possibility of publishing his novel, Icosameron, which he had started composing in Venice(36) in 1782. This is the firm his friend Max Lamberg had used to print his books.1784

On January 18th he was in Prague.

Francesca Buschini, February 7, 1784, poste restante at Vienna (37) :

Francesca Buschini, February 28, 1784, poste restante at Vienna (38):

. . . . I am glad you are together with your brother [Francesco] and I only hope you will have enough money by May to come to Venice.

. . . So you had a lot of fun during Carnival and you assisted at four masked balls where 200 ladies were present, and you danced minuets and contradances to the astonishment of Ambassador Foscarini, who told everyone that you were 70 years old while in reality you are not even 60; you had better laugh about it and tell him he must be blind if he doesn’t see so himself. Together with your brother you attended a great banquet given by the same ambassador. You began to sum up what you had to eat and then you stopped for fear that at such a story my mouth would water. That is a very true thing. You are quite right in saying you and I have two peculiarities in common: you, that you always talk about eating, and I that I am always in need of money. You say you read my letters to your brother and that he sends me his greetings. Please give him also my regards and thank him. Tell him that I would write to him that, in case he comes with you to Venice, he can live with you in your house. You can honestly say so because the chickens remain always in the attic [together with Casanova’s books!], therefore there is no chickenshit; and we will take care that the dogs [Patagnan and Aïda] won’t cause any damage. The furniture is still almost complete. Only one cupboard, the small bed you bought for your nephew, and the mirror have gone; the rest is still as you left it . . . .

For Giacomo it was the beginning of two new perspectives. Two, because it was at this banquet that he met Count Joseph Waldstein, whose librarian he would eventually become, and at the same time Ambassador Foscarini offered him a position in the embassy.

For Francesco it was the introduction to a successful continuation of his artistic work. In Paris he was peintre du roi; in Vienna he would become more or less peintre du prince for the prince and prime minister Wenzel Kaunitz-Rittberg. Kaunitz became very fond of Francesco. Of Kaunitz it is told(40) that he had a parlor next to his office where he could sit in a glass enclosure for fear of drafts and diseases, while his visitors would sit at the other side of the window. At Kaunitz’s side one could see paintings by the best artists and especially by Francesco, of whom the prince spoke with the greatest distinction, saying that he was the only painter who worked the way he, the prince, wanted to see it. And Count Zinzendorf wrote in his Diary (June 22, 1794) that Francesco was the only one allowed to come and see the dying prince. "He will not even see his children, only Casanova now and then."

Another of Francesco’s high-ranking clients was the Prince von Nassau-Siegen, whom Giacomo had met in Spa. Zinzendorf wrote on March 31, 1792, in his Diary that he had seen at Kaunitz’s a big painting by Casanova, covering a whole wall, depicting Joseph II, followed by his generals, routing the Turks. "Casanova made this painting for the prince of Nassau, who pays 900 ducats for it." And Lamberg tells about paintings which Francesco made for Catherine II of Russia:

[Francesco Casanova: Poststation in Italy. Photo: M. Leeflang]

For Giacomo the banquet was an opportunity to get to know Count Waldstein. The Prince de Ligne wrote about this meeting(44):

The Foscarini track went better. "I placed myself at the service of Mr. Foscarini, ambassador of Venice, in order to write communications for him," Casanova writes in his Précis de ma vie (46). But this engagement wouldn’t last long. "Two years later (on April 23, 1785), he died in my arms, killed by the gout which extended to his breast."

Casanova knew the Foscarini family from Venice. Two brothers were chosen ambassadors to Vienna, first the younger one, Niccolò (March 1777 to October 1781), then Sebastiano (October 1781 until his death). When Niccolò was appointed, someone from Vienna, maybe Prince Kaunitz, asked Casanova to send "a portrait" of the new ambassador. Casanova obliged, and his able pen drew in two pages, of which he kept a copy(47), a sharp picture of the talents of the new ambassador: it will be his first embassy, great orator, does his homework, beloved and esteemed, pleasant and popular, of rich family, exact and dutiful. "If he does something, he does it 100%, but that doesn’t mean he neglects his pleasures. He frequents gatherings of old politicians, of young people of the world, and the most attractive girls of the city. He has a beautiful mistress, and they both love each other, but he is so charmed with the opportunity to prove his talents in this embassy that I think he will leave her behind without regrets."

Max Lamberg made use of the Venetian ambassador in a peculiar way. Lamberg had proposed Casanova as a member of the Literary Society of Hesse-Hombourg and when the diploma of this society arrived, he did not send it directly to Casanova in Venice but to the embassy in Vienna, pretending not to know the whereabouts of Casanova and requesting the ambassador to forward it to wherever this citizen, now honored for his knowledge and literary learnedness, might live. At the same time he informed Casanova of what he had done. Clearly he hoped the honor bestowed on Casanova would be more widely known as a result of this diplomatic detour. In any case, the maneuver worked, and Casanova received his diploma and the congratulations of Foscarini (48).

When Casanova started his duties, the Venetian embassy in Vienna had just become the focus of a small international issue. The Netherlands had on January 9, 1784, more or less declared war on Venice, and both parties sought the intervention of Joseph II. The Dutch and the Venetian embassies had work to do.

The ambassador spoke very little French(49), which in those days was the diplomatic language. Maybe Foscarini was only too glad to get some help from someone who did. For Giacomo it offered a new opportunity to write and publish. The Venetian embassy had been supplied with the underlying documents which Casanova could freely consult.

In a year’s time Casanova produced several booklets and articles (50) about the affair, beginning with the Historical-critical Letter About a Known Fact Depending on a Little-known Cause, printed in Dessau in 1784. The affair appealed to Casanova because he knew both Holland and the Zanovich brothers, who caused the row, very well. According to the memoirs, Primislao Zanovich drew the 18-year-old Lord Lincoln, son of the Duke of Newcastle, into play and mulcted him of the enormous sum of 12,000 guineas. Fully 3,000 were paid in cash, and Lincoln signed three bills of exchange for 3,000 each, payable at intervals of several months. The Zanovich were ousted from Florence and Casanova with them. These bills of exchange would play a role in the Historical-critical Letter.

What had happened?

Late in November 1772 the brothers, Count Primislao Chiud Zanovich and the younger one, Stjepan Zanovich, arrived in Amsterdam. They made friends with two merchants from Berlin, Pierre Chomel and Carl Henri Jordan, who had set up a joint business in March 1770 for the duration of six years. Primislao presented recommendations signed by a firm in Lyon and confessed that the Zanovich brothers were temporarily in financial trouble, which caused delay of their plans to improve their estate in the Venetian part of Albany. In exchange for a bill of exchange for 3,500 zecchini, Chomel and Jordan helped the brothers with 27,000 guilders, of which a part, in diamonds, was temporarily deposited with a Genoese banker. The merchants were furthermore assured by the Zanovich brothers, who said a ship loaded with their wine would soon arrive in Holland. They paid the hotel bill for the brothers and supplied them with money for the return trip to Italy. In the meantime notice came from London that the bill of exchange was forged and that they should advertise this in the newspapers in order to prevent further trouble.

Jordan immediately left for The Hague in order to have the Zanovich brothers imprisoned for debt. Again Premislao managed to reassure the somewhat naïve merchants: "I would never have remained here quietly had the bill been forged. I know such a thing could lead to the scaffold." In 1772 the brothers left undisturbed for Italy, where they tried in vain to get hold of the diamonds. In December 1773 Primislao announced to Chomel and Jordan that a first-class merchant’s firm in Budua hoped to do business with Amsterdam, and a little later this was confirmed by a letter from Nicolo Peovich & Co. A fake company, as it would turn out later. In the meanwhile Zanovich went to Naples where the Venetian ambassador, Simone Cavalli, was in financial trouble. The firm Peovich was mentioned again, and in exchange for whatever Zanovich did for Cavalli, the consul signed with his official title, residente veneto, two guarantees for the fictitious house of Peovich and its associate Zanovich.

These signatures persuaded Chomel and Jordan to make the diamonds in Genoa payable and to return the false bill of exchange after Peovich & Co. had agreed to assume the debt of Zanovich. The Amsterdamers even extended a new credit of 6,000 guilders when they heard that a certain Antonio Deglich (another fake) would send a ship, the Minerva, to Amsterdam loaded with olive oil and wine. "The Minerva of Peovich was born in the brain of Zanovich as the Minerva of Homer in that of Jupiter," Casanova remarked. Peovich suggested the ship be insured in Holland and England for 130,000 guilders. From their contacts in Lyon, Chomel and Jordan heard that, though some years ago the Lyonese bankers had recommended Zanovich, they had changed their opinion. Now they warned the merchants in Amsterdam not to do business with Zanovich. They also said Mr. Peovich was none other than Stjepan Zanovich. Also Cavalli, now representative in Milan, became more prudent and advised not to extend any more credit before the ship had arrived. However, when Cavalli received alarmed letters from Amsterdam, he said he was now certain the cargo was ready to be shipped.

In 1772 Peovich & Co. wrote that, to their great regret, the Minerva had to be regarded as lost and suggested the merchants make a claim on the insurance. By now Chomel (Jordan had returned to Berlin after the expiration of his six-year association contract) finally fully realized he had been duped.

In June 1776 Jordan saw—small world—in Berlin a "Count Zanovich Babbindon Czernovich, author of the Lettere Turche, who called himself Bonenski," and who was on very good terms with Frederic II and the crown prince. He was almost sure this was Stjepan and asked Chomel to quickly send the portrait which Stjepan had given them in 1772. Poor Chomel couldn’t find it, and besides, they had signatures of Primislao only, because Stjepan had always kept himself a bit in the background.

Until now the affair had been purely private, but Chomel tried to get help from the Dutch States General, making good use of the signatures of Cavalli, who officially represented the republic of Venice. This was not easy, because Chomel was not Dutch, and although he had lived in Amsterdam for almost 15 years he wasn’t even a poorter of this city. However, he found protection with the first pensionaris of Amsterdam, van Berckel, and the city of Amsterdam was powerful in the States General. The affair was small, but the principles of fair trade were jeopardized, so finally, in 1777, the Dutch consul in Venice was officially asked to intervene. To no avail. Then Chomel asked the Dutch ambassador in Vienna to intervene and to try to interest Joseph II.

Venice became uneasy and appointed a special court of justice consisting of 25 senators to deal with the matter, and in the meanwhile Cavalli was suspended. Procurator Morosini apologized to Cavalli, saying he had tried everything to prevent this move and hoped that Cavalli would manage to clear himself, as it was really Zanovich who was the culprit. Zanovich felt the heat and wrote also to Cavalli, assuring that he would go bury himself at the ends of the world (he chose Russia for this purpose). In a secret procedure the Venetian Council of Ten decided after no fewer than 50 sessions that Cavalli was innocent of criminal behavior, and he was appointed resident in London. In August 1778 the Venetian court of justice established that the Minerva and the Peovich firm were both fraudulent inventions. Primislao Zanovich was banned from Venice forever and Stjepan for 10 years. Their "fortune" was confiscated and could "possibly" be used to indemnify the Amsterdam merchants. Of course the "fortune" had disappeared, and the official surveyor whom Venice had sent to Budua to measure the land of the Zanovich family had been harassed, which gave Venice reason to let the heads in Budua cool off.

Amsterdam didn’t understand the Venetian course of justice and was furious. It became a matter of democracy over against aristocratic tyranny. Several resolutions of the mighty city of Amsterdam were adopted by the States General, thus escalating the affair.

For Stjepan Zanovich the bluff poker hadn’t ended. In Berlin his playing habits had made him non grata, in Vienna he had had some unpleasant adventures, and now he was back in the Dutch republic. The Prince of Albany, as he now called himself, was imprisoned for debt for five months in Groningen, but he managed to talk himself out of it and into the protection of the magistrate Fockens, who paid all his bills. In the last days of 1781 he called on the surprised Chomel. He proposed to act as an intermediary in order to press Cavalli to pay reparations, and he even offered 10,000 zecchini—which he most probably didn’t have—if Chomel would let the affair rest. Anyway in February 1782 he emerged in London where he gave another try to the bills of exchange with the father of Lord Lincoln (the son had died). It didn’t work, and his plan to provide Lord Lincoln’s money to Cavalli, who could indemnify Chomel with it, failed.

In 1781 the States General had decided to send an "able person," Frederik Tor, to Venice. Tor tried to initiate a civil procedure against Cavalli after the criminal process exonerated him, but Tor was eventually recalled, having reached no visible results.

Now Venice asked Joseph II to intervene, and when the States General sent Count Wassenaer to Vienna as plenipotentiary minister, Vienna had become the center stage of the affair. Wassenaer had a lucky hand when he recruited to his service the former secretary of Giorgio Pisani, a patrician who had been condemned for his attempts to reform the calcified institutions in Venice. He sent this secretary to Venice, who discovered Cavalli continued to advise the Venetian government. Wassenaer managed to get hold of a document—copied while Cavalli, back in Venice, slept—which would be the basis for an extensive diplomatic nota from Venice to the Austrian Prince Kaunitz. What Wassenaer didn’t know was that the Venetian inquisitors had in the meanwhile also engaged this same ex-secretary of Pisani as a double-agent into their service.

Then, in January 1784, the States General came to a long-expected resolution: There would be a test to see if Venice would react upon the arrest of as many Venetian ships in Dutch harbors as would be sufficient, if sold, to indemnify Chomel and Jordan, who claimed 68,000 guilders including interest. In particular the ship Il Corriere Marittimo should be impounded. The Prince of Orange was requested to inform the commanders of Dutch warships bound for or sailing in the Mediterranean to take under their protection all Dutch commercial vessels.

But the chickens were counted before they were hatched. No Venetian ships were to be found; even the Corriere had left two months earlier. And when Wassenaer reported from Vienna that Venice seemed willing to cooperate, the execution of the resolution to wage war was postponed by one month but never came into effect (51).

This was the situation when Casanova stepped in and took his share in influencing public opinion with his pamphlets.

In the end the affair died out. Holland had more important matters on its hands. No ships were taken, no money was paid, and Chomel in vain kept writing letters until 1791.

Now back to Casanova’s own story.

He wrote the Historical-critical Letter not in French but in Italian, as mentioned in Lamberg’s letter of April 21 (52):

In the end the Historical-critical Letter was published in French and not in Italian.

Thanks to the Casanovist Gustav Gugitz, who copied in the Dessau library the manuscript memoirs of Heinrich Wolfgang Behrisch(53), we know it was he who translated Casanova’s Letter, which was published in the Buchhandlung der Gelehrten in Dessau. "My sojourn in Dessau lasted a year and a day during which I translated and published . . . La Lettre sur un sujet connu dépendant d’une cause peu connue . . . from Italian."

The booklet was refused by the censor. Non admittitur impressio (54). Casanova appealed to the president of the commission, van Swieten, and then to Prince Kaunitz(55), proposing to use a fictitious imprint. Kaunitz probably took care not to involve Austria in the conflict. Approval by the censors could have been seen as approval of the Venetian side. Anyway, by April 24th Casanova was ready to do business in Dessau. He made a proposal to Le Roy de Lozembrune, a collegue of Della Lena and teacher of French in the Theresianum, to direct the printing. Casanova would send money to cover all expenses. But Le Roy himself couldn’t do the job: He said he didn’t feel capable of it, and besides he had other things to do(56). It was probably Berisch who in the end took care of the whole enterprise, and when the booklet was printed, the Letter was dated "à Hambourg, ce 12 Mai 1784."

Francesca Buschini, March 20, 1784(57):

And who were the two ladies? Was one of them perhaps the woman he wrote a poem for, entitled "Verses from Giacomo Casanova in love with C.M." ? And the other one perhaps the "little Kaspar"? To Caton M. Casanova refers in his memoirs (59):

Little Kaspar, who will later become a favorite of Joseph II, is mentioned in another of Caton’s letters(61):

The books may have been dearer to Giacomo than the girl. Anyway, though Francesca continued writing for some time, Casanova kept silent for a year and a half and sent a few last letters only in 1786 and 1787.

So from this point on we have to do without Francesca’s echoes. But for this period Lorenzo Da Ponte gives us some information. In 1784 he had just finished his first opera libretto, Le Riche d’un jour, on music by Salieri, and he would soon begin collaborating with Mozart. Da Ponte published his own Memoirs in New York City in 1829-1830. He must have had access to the first edition of Casanova’s Histoire de ma vie, because he comments on the truthfulness of memoirs in general and adds about those of Casanova: "I don’t say this to reduce by one iota the merits of Giacomo Casanova or those of his Memoirs which have been written gracefully and which I read with pleasure, but knowing this extraordinary man better than anybody else, I can assure my readers that love of truth is not the essential value of his work."

On the other hand, Da Ponte himself wasn’t always trustworthy in his own Memoirs. One of his editors commences his preface with the words: "The Memoirs of Da Ponte are dominated by the omnipresence of lies. Our man lies like he breathes, apparently in an instinctive way, by pure pleasure and without any clear goal. Certain histories he tells, certain conversations he reports are so thinly related to reality that one doubts if they were ever meant to be believed . . . . (69)"

Nevertheless they are too interesting to be omitted.

Da Ponte writes that one day, while strolling with Salieri on the Graben in Vienna, he saw: an old man who looked at me in a very peculiar way. While I tried to place him in my memory he stood up and came quickly towards me. It was he! It was Casanova who called my name. "Dear Da Ponte, what a joy to see you again." He lived in Vienna for a couple of years during which neither I nor anybody else could say what he did and what he did for a living. I saw him often; my house and my wallet were open to him . . . . Some time later, walking with him on the same street, I suddenly saw him frown; he left me standing there and quickly went in pursuit of a man whom he grabbed by the collar, and he cried out loud, "Now I have got you, murderer!" An ever-growing crowd assembled, attracted by this strange aggression. Baffled, I stood there awhile inactive, but after two minutes of reflection I ran toward him, grabbed him by the arm and led him away from the row. Then he confided to me that this man, Gioachino [Gaetano] Costa, was the servant who had run off with his trunk and his treasure [taken from Madame d’Urfé in 1760 in Paris]. Valet of a grand seigneur of Vienna [Count Hardegg], and having added to his low function the profession of poet, [Costa] was one of those who had honored me with their diatribes during the time I was in the favor of Joseph II. We continued our walk, and we saw Costa enter a café, out of which soon appeared a waiter who gave a piece of paper to Casanova. It read in a few lines: "Casanova, you have stolen, I have cheated/You the master, I the student/In your art I too am prudent/You gave me bread, I gave you cake/Hold your tongue for heaven’s sake." These few words had a great effect. Casanova reflected; then, bursting out laughing, he bent over to my ear saying: "The scoundrel is right." Then going toward the café, he signaled to Costa to come out and join him and both, side by side, strolled away talking as quietly as if nothing had happened. A few minutes later they shook hands several times like two intimate friends and parted. When Casanova came toward me he wore on his finger a cameo I hadn’t seen him wearing before and that—bizarre coincidence—represented Mercury, god of thieves. I suppose this cameo was the only piece of wreckage he had been able to recover of that deceit (70).

In another episode, after having suggested that Casanova’s main income came from his card games and that Della Lena and Giacometto Foscarini, the son of the ambassador, were his main prey, Da Ponte says that Casanova:

One morning, while at the emperor’s for affairs of theater, our Giacomo asked for an audience. He enters, bows his head and presents his memorandum. The emperor unfolds it, but perceiving its length, he folds it again and asks what he wants. He explains his projects and develops the epigraph Cur, quia, quomodo, quando; but Joseph II wants to know his name. "Giacomo Casanova," he says, "is the humble person who solicits Your Majesty’s favor." Joseph II remains silent for a few moments, then says with his usual friendliness that Vienna doesn’t like such spectacles; he turns around and resumes his writing. The solicitor added no word and retired humbly. I wanted to join him, but the emperor called me back, and after having repeated three times, "Giacomo Casanova," he started talking theater with me again (71).

This attitude, of course, is quite in contrast to his impudent conversation with Joseph II regarding the sale of titles of nobility.

We meet another acquaintance of Giacomo in a letter dated April 26, 1784 (73). It is signed by "Teramene," the Arcadian name of Alphons Heinrich Traunpaur(74), Chevalier d’Ophanie, introduced to Casanova by Lamberg. Traunpaur was a temporarily retired professional soldier with literary ambitions who had moved to Vienna in November 1783. The letter deals with a rather prosaic matter: the pawning of some winter clothes of Giacomo. Casanova had gone to take the bath in Meidling(75). As spring had arrived he did not need his winter clothes, and he expected that his red fur coat, a muff, a suit, and a black velvet overcoat would be worth 50 guilders. ApparentlyTraunpaur was kind enough to do the job, paid six guilders fee to the pawnhouse, charged one for the taxi fare, and held the clothes and the remaining 43 guilders available at his home.

Traunpaur, also signing his poems with "Partunau," took the title "Chevalier de Seingalt" for a family affair when he had printed, in May 1784, his welcome salute to Francesco: Letter to Monsieur François de Casanova de Saint-Gal, revered painter of the King of France, on the occasion of his stay in Vienna (76).

However, the friendship would not endure. Casanova accused him of plagiarism (77), and in 1788 Lamberg writes to Casanova (78): "You did well to break with the rhymester Traunpaur, the stupidest thief of other people’s ideas. I am sorry to have sent him to you; leave him alone and break off all contact with him. If he keeps writing to you, answer him dryly that Tragedy never responds to Comedy or even better: to Farce."

In 1784 Casanova planned to write a sequel to his History of the Polish Troubles. He had a prospectus printed, Notice to Lovers of History [Avis aux amateurs de l’Histoire](79) in which he says:

Or is there? Had he planned perhaps to use the material of the unpublished part of his History of the Polish Troubles (80), reviewed and updated with more recent events?

Anyway, at this time he was reminded of the history of his own troubles by the printer of the Polish Troubles, Valerio de’ Valeri. The printer claimed Casanova had failed to deliver the continuation of the History; he successfully sued for 3,000 florins Count Torres, who had been willing to act as a guarantee. A furious Casanova wrote (dated Vienna, July 23, 1784) a Declaration of Giacomo Casanova, written by himself eleven years after a contract was signed by him and Valerio de’ Valeri, printer in Gorizia (81). In this declaration, Casanova states it was not he, but Valerio, who had violated the contract by failing to pay the author’s fee. Giacomo tried to start an appeal in court to free Torres of the burden. It is not known whether he succeeded.

Then Casanova picked up another idea which had come to him during his last annoying years in Venice, when he was discontent with everything. When the world is against you, why not shape your own world? It would be the Icosameron, and on April 15, 1785, he confided to Lamberg that he had already finished two parts. "It will consist of two volumes of 500 pages each, and at the end I will be able to say, like Ovid said about his Metamorphoses, ‘this is a work which will bring me immortality (82)." Casanova kept his word and finished the novel in 1787, but it didn’t bring him the expected fame.1785

In between all these projects there was time for social contact. We get a glimpse of this when the lieutenant Cusani invites him, in verse, for a luncheon at Schönbrunn while giving him the choice between two dates. Casanova answers in a long ballad(83), excusing himself for both dates. On the first day he has a prior engagement: an invitation to Antonio Collato’s, "where there will be aristocratic people and a concert; there is a pretence of culture but it is just a cover-up for love-plays and jokes about and against women." On the second day he is expected at the ambassador’s:

These are the invitations I have received and that I must accept, so please understand when I tell you I cannot come to you.

Three letters to Domenico Tomiotto de Fabris, an old friend whom he had gotten to know a long time ago in Padua, whom he had met several times later in life, and who was now governor of Transylvania, led to no result. In one of them Giacomo had dusted off his old idea of becoming a monk. Fabris finally answered on June 10th(84) to Casanova’s last address in Vienna, Im Heidenschusse wo der Türk: "It pleases me to hear that you begin to contemplate seriously the misery of humanity. It needs more than the dress of an abbé, as you plan, to make a monk. At our age we shouldn’t think much of writing, but of contemplation and death."

The main reason for Casanova to write to Fabris was to offer his services as a secretary, but Fabris has no vacancy: "Thanks very much for your friendly proposition, but I have in my office 18 secretaries who kill me by forcing me to read and sign."

Soon after this letter Casanova leaves expensive Vienna in a hurry and seeks refuge with Lamberg in Brno. From there he leaves for Carlsbad hoping that Princess Lubomirska can help him get a position at the Academy in Berlin.

Lamberg suggests that on the way he pay a visit to his friend Opiz, ex-Jesuit and now inspector of finances in Bohemia. In an accompanying note, Lamberg advises Opiz (85): "A famous and revered man, Mr. Casanova de St. Gall, carries, dear friend, my visiting card which he will hand to you and Mrs. Opiz. Getting to know this amiable and rare man will be a great event. Be nice to him and friendly . . . . Write me about him, and if you can, give him a recommendation for Calsbad."

On August 5th Lamberg writes to Opiz:

It must have been around August 10 that this meeting took place, where Waldstein and Casanova came to an agreement. At that time Giacomo wrote a note (86) to Della Lena, excusing himself for not having had time to go to the Theresianum to say goodbye and to thank him for all his help. Casanova planned to do that in January. He begged Della Lena to pick up his poste restante letters and send them to—the first time he writes his new and final address—"Mr. Casanova chez M. le comte de Waldstein

2) Casanova Archives: Marr 16 H 39. retour

3) Prince de Ligne, Mémoires, lettres et pensées, éd. François Bourin, Paris, 1989, p. 794. retour

4) Published by H.Watzlawick in the Casanova Gleanings, Nice, 1979, p. 6. [Marrco 40-39]. retour

5) Cf. Casanova Archives, respectively Marr 8-194, 166, 169, 184, 173, 176 and 168. retour

6) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 4-64. retour

7) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 31-49. retour

8) Cf. H.Watzlawick: ‘Casanova, Madagascar and Spa’ in l’Intermédiaire des Casanovistes, Roma, 1987, p. 1. retour

9) The Listes des Seigneurs et Dames venus aux Eaux Minerales de Spa, appearing since the middle of the century for the sake of convenience of guests and commerce. During the season the Lists appeared frequently and kept count of the number of visitors. Thus Casanova was mentioned in the 25th issue as the 627th guest of the year. The Lists contained advertisements as well. They can be consulted in the Bibliothèque communale of Spa. retour

10) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 34-4. retour

11) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 16 K 47. retour

12) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 3-64. retour

13) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 16 i 1. retour

14) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 16 i 14. retour

15) Cf. for the business with Conty: Casanova Archives: Marr 12-57, 4-28, and 16 F 4. retour

16) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 9-50. retour

17) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 12-40. retour

18) Cf. the summary of a legal writ in catalogue no.433 of the antiquariat Henning Oppermann, Bâle, 1932, lot 205a. retour

19) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 8-163, d.d. october 18, 1783. retour

20) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 18-23. retour

21) In his Lettres à Faulkircher [Marr 39-1] he writes. "In 1783 I stayed in Paris for three months and in Fontainebleau for a week, and I departed with a passport of mr de Vergennes accompanied by my brother. Go and ask in Vienna. You’ll find him every day at the table of prince Kaunitz." retour

22) Cf. Casanova: A Leonard Snetlage, 1797, where he treats the word Aërostate. The casanovist Charles Samaran found records of a session on november 22nd 1783 of the Academy of Sciences, where Condorcet was present. He suggests that Casanova might refer to this session. But given the fact, proven by a letter (see below), that the brothers arrived in Frankfurt at the latest on november 26, this is hardly possible. It is more likely that they left Paris soon after receiving their passport and that Giacomo was present at a different meeting of the Academy, held prior to the first ascent. This is in accordance with his remark that the meeting took place "a few days after the death of the famous d’Alembert." This death occurred on october 29. So most probably Casanova has not witnessed the ascent himself. If he had, he would have mentioned it in his correspondence, but Francesca nor Zaguri reflect the subject in their letters, nor does Giacomo in his next message to Della Lena. The fact that Casanova states in 1797 that his encounter with Franklin took place in the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres may have been a slip of the pen, as in his letter to Della Lena (november 28, 1783) he calls it the Accademia delle Scienze. retour

23) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 13 Y 3. "Augusta de 26 9bre 1783" retour

24) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 13 B 3, 13 B 4, and 13 B 6. retour

25) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 8-185. retour

26) Published by Bruno Brunelli in G. Casanova e l’Abate Della Lena, Venezia, 1931. The english translation (by Gillian Rees) is taken from Pablo Günther, The Casanova Tour, Heidelberg, 1996, p. 103. retour

27) Casanova Archives: Marr 12-45. retour

28) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-189. retour

29) Lying seems to have been a favorite pass time for Giovanni. Without blushing he wrote in 1761 from Rome to Giacomo in Paris: "J’ai été chez l’Abbé de Moncada que j’ai vu pour la première fois de ma vie et lui tout de même ainsi ne me connoissant pas il m’a pris pour un Cavallero il n’est pas nécessaire de te dire toutes les menteries que j’ai étalées car je ne m’en souviens pas, je me souviens seulement que je n’ai pas dit un mot de vérité ..." (Marr 13V5). retour

30) Casanova Archives: Marr 13 V 8. retour

31) Giovanni Casanova Discorso sopra gl’Antichi e varj monumenti loro per uso degl’alunni dell’Elettoral Accademia delle Bell’Arti di Dresda, Leipzig, 1770. retour

32) Giovanni Casanova: Collection de Camées, Pierres gravées en creux, Pâtes antiques en relief et en creux, formée par M. Casanova Directeur de l’Academie Electorale des Beaux Arts à Dresde, et acquisée par Sa Majesté Catharinae II, Imperatrice de toutes les Russies" (Hermitage, inv.n? 47090). retour

33) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-23. retour

34) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-50. retour

35) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-36. retour

36) Casanovas letter to Lamberg, dd april 15, 1785, of which Lamberg sent a summary to Opiz [cf. Opiz copy of Lambergs "92th letter" in Opiz’ manuscript Correspondence, vol. V, pp.107-112. [Marr 40-49] retour

37) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-162. retour

38) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-182. retour

39) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-183. retour

40) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-76, letter from Lamberg to Casanova. retour

41) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-83. retour

42) Anna Jameson-Brownell ( Dublin 1794-Ealing 1860): Celebrated female sovereigns, 1821, vol.II, p.328. retour

43) Cf. Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Souvenirs de Mme Vigée-Lebrun (Paris 1835.1837), vol. II, p. 205s. retour

44) C.J. de Ligne, op. cit. p.794. retour

45) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-38. retour

46) Casanova Archives: Marr 21-1. retour

47) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-28. retour

48) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-52 (Lamberg informs C. that he sent the diploma to Vienna), Marr 12-58 (Foscarini forwards the diploma, sends his congratulations and includes Lambergs request to Foscarini [Marr 2-51]). retour

49) Casanova Archives: Marr 4-42. retour

50) Lettre historico-critique sur un fait connu, dépendant d’une cause peu connue, [Dessau], 1784; Exposition raisonnée du différent, qui subsiste entre les deux republiques de Venise et d’Hollande, nov. 1784 and in a revised version jan. 1785; Esposizione ragionata della contestazione, che susiste tre’le due republiche di Venezia, e di Olanda, 1785; Lettre a messieurs Jean et Etienne L[usac, of the Gazette de Leyde], contenat des observations sur le narré de l’affaire, qui a donné lieu au différent entre la République de Venise & celle d’Hollande publié dans les Nro. XXI & XXII de leur Gazette, Gazette de Leyde, march 31, 1785 and Gazette de Cologne, april 19th 1785; Supplément à l’Exposition raisonnée du différent qui subsiste entre la République de Vénise, & celle de Hollande, [march] 1785; and several articles on the same subject in the Osservatore Triestino, jan 1st through february 26, 1785. Cf. H.Watzlawick: "The Zannovich Pamphlets, notes for a revision of the Casanova Bibliography" in Casanova Gleanings XX, Nice, 1977, pp.63-70. retour

51) Cf. Dr. E.O.G. Haitsma Mulier: "De affaire Zanovich. Amsterdams-Venetiaanse betrekkingen aan het einde van de achttiende eeuw" in Amstelodamum, Jaarboek 72, Amsterdam, 1980 of which the above mentioned Affair is extracted. retour

52) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-38. retour

53) Cf. J.R.Childs: Casanoviana, Vienna, 1956, p. 71 and H. Watzlawick: "A touch of madness - le chevalier de Béris" in L’Intermédiaire des Casanovistes, Rome, 1984, pp. 9-14. retour

54) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 32-2. retour

55) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-21. retour

56) Casanova Archives: Marr 12-91. retour

57) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-200. retour

58) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-195. retour

59) Casanova: Histoire de ma vie, éd. Brockhaus/Plon, Vol.1, p.36 and Vol.11, p.282. retour

60) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-52. retour

61) Casanova Archives: Marr 4-20 and Marr 12-64, d.d. july 16th, 1786. retour

62) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-174. retour

63) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-167. retour

64) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-181. retour

65) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-175. retour

66) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-170. retour

67) Casanova Archives: Marr 3-62, letter dated may 11th, 1784. retour

68) Casanova Archives: Marr 8-171, quoted by F.Buschini. retour

69) J-F. Labie in Mémoires et livrets / Lorenzo da Ponte, Le Livre de Poche, Paris, 1980, p.11. retour

70) Da Ponte: Mémoires, op.cit. vol.3, p.148. retour

71) Da Ponte, op. cit. vol.4, p.258. retour

72) Casanova Archives: Marr 9-27. retour

73) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-22. retour

74) Cf. H. Watzlawick: "Et ille in Arcadia / Traunpaur, chevalier d’ophanie" in Casanova Gleanings XXIII, 1980. retour

75) Casanova Archives: Marr 16 F 12, a hotel bill for a stay from may 29th till june 3rd 1784. retour

76) Casanova Archives: Marr 36-24, 25, 26 and 30. retour

77) In his Echantillons envoyés par un observateur barbaresque à sa belle au bout d’une année de séjour dans une Capitale policée etc, 1784, Traunpaur had used a few of Casanova’s favorite lines like ‘de rivage en rivage’. retour

78) Casanova Archives: Marr 2-53. retour

79) Casanova Archives: Marr 36-18, 19 and 20. retour

80) Casanova: Istoria delle turbolenze della Polonia, Tom. II, Parte II, [Marr 26-9]. The existence of the manuscript was signaled already by A. Mahler in 1905, but it was published only in 1974 by G. Bozzolato in Casanova: uno storico alla ventura. retour

81) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 17 A 27. retour

82) Cf. Opiz correspondence with Lamberg: march 24, 1786 in which Lamberg quotes Casanova’s letter ofapril 15th, 1785. retour

83) Cf. Casanova Archives: Marr 17 C 3 and 5. retour

84) Casanova Archives: Marr 12-98. retour

85) Opiz manuscript copy of his correspondence with Lamberg d.d. july 30, 1785. retour

86) Lettre to Della Lena, august

1785; Casanova Archives: Marrco 40-48. retour

Copyright by Marco Leeflang, Utrecht. 1997-2001.